Centre St. Redesign: West Roxbury, Boston

Jackson, Jude, Amelia, Max, Liam

Introduction

While there are many elements required for effective traffic design, safety is paramount. The only effective way of controlling safety is to create infrastructure that self-enforces speed and awareness. If drivers have a comfortably wide and straight 15-foot lane, they will naturally feel inclined to travel at higher speeds. If drivers are forced to travel in a narrower, 10-foot lane with frequent curves, they will have no choice but to travel at lower speeds. There are many adjustable design features used to affect driver behavior that must be carefully considered to achieve the intended traffic patterns.

Centre Street is an urban arterial street in West Roxbury, Massachusetts with two lanes per direction (2+2) and curbside parking on both sides. A number of businesses line both sides of the street, which is periodically cut by intersecting streets and driveways. Centre Street serves as a high-volume throughway from Lagrange Street to the West Roxbury Parkway, as well as a way for local residents to get to the numerous, lower volume side streets. Given the strong residential presence directly adjacent to Centre Street and the density of businesses, pedestrian accessibility and safety is a major concern.

There are seven signalized intersections with crosswalks (Figure 2), some required to accommodate pedestrians and others for the higher volumes of traffic. Those that only provide safe crossing durations, rather than necessary traffic control, impede the flow of traffic and make pedestrians wait excessive amounts of time. If a pedestrian wishes to cross anywhere besides one of these intersections (Figure 1), they are forced to cross four lanes of traffic and risk involvement in a deadly “multiple threat” accident. A car in the first lane might stop for the pedestrian, however, this car might block the vision of a car in the second lane, leading to a collision with the pedestrian. This phenomena is compounded in a four lane scenario as evident by a 2015 accident, in which a man was sent to the hospital for several months after attempting to cross Centre Street’s multiple lanes of traffic. The two-lane per direction and no median design gives cars the feeling of excessive space, promoting speeding, allowing passing, and further increasing the risk to crossing pedestrians. Cyclist safety is also neglected on Centre Street, made apparent by the complete lack of cycling infrastructure.

To better serve the local businesses, residents, and active commuters, Centre Street is in need of a total redesign with a strong “complete streets” mentality. Through strategic planning, design, and operation, Centre Street can provide safe and effective mobility for users of all transportation modes.

Figure 1 – Crossing four travel lanes and two parking lanes with nothing but a yield sign provides an extremely stressful environment for pedestrians

Figure 2 – Section of Centre Street to be redesigned

Vision/Objectives

For decades, society’s paradigm for streets has revolved around motor vehicles and how to get drivers to their destinations as quickly as possible. Whether it be highways, local streets, or even parking lots, the majority of our infrastructure caters to cars and trucks rather than more sustainable forms of transportation such as cycling or walking. A lack of effective cycling infrastructure and a plethora of dangerous pedestrian crossings makes for undesirable streets, negatively impacting local residents, businesses, and drivers who are tasked with avoiding accidents in a rigged system. But this narrow-minded mentality is all beginning to change.

While most communities now have policies to help develop “complete streets”, a street that safely accommodates all forms of transportation, multimodal transportation efforts in the Boston, Massachusetts area have been slow to catch up. Centre Street in West Roxbury, a particularly unaccommodating street to anything but motor vehicles, is in need of a “complete streets” focused redesign. With careful forethought and manipulation of the roadway’s infrastructure, traffic on Centre Street can be slowed down and made more accessible to pedestrians and cyclists. Not only would this improve human safety, but it would also boost business development and real estate appeal.

In line with Go Boston 2030’s goal of making Boston’s neighborhoods connected by safe and reliable multimodal transportation, the Centre Street redesign will focus on slowing traffic to create a safer experience for all. By applying a road diet approach and consolidating travel to one lane in either direction, traffic will be forced to slow down and pedestrian crossings will be inherently safer. Combined with new cycling infrastructure to provide cyclist access through the area, Centre Street will be transformed into a safe and accommodating commercial throughway for all types of users.

Design

Typical Cross Section

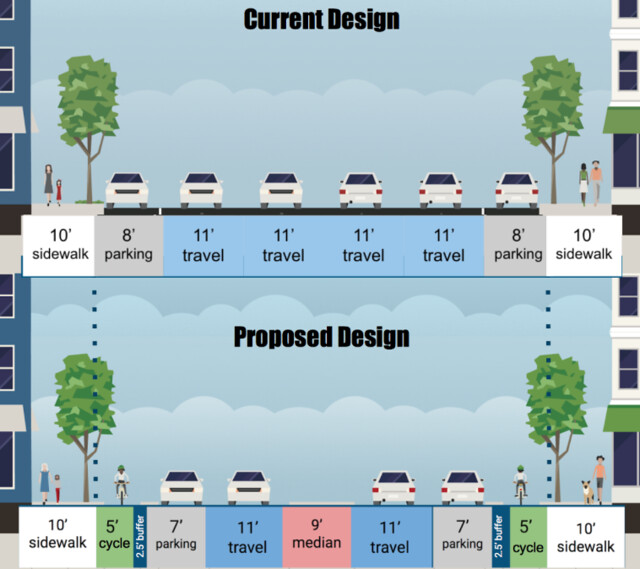

In the typical cross section, shown in figure 3, the 10 foot pedestrian crosswalk will remain at that size in order to continue accommodating the foot traffic accessing the commercial areas along the road. Some of the area along the sidewalk next to the cycle track will be designated for trees, streetlights, and bicycle parking. After 10 feet, the sidewalk will transition to a cycle track located at the same elevation as to allocate as much space as possible for both pedestrians and cyclists. It is assumed that the occasional tree and streetlight, as well as differing pavement surfaces, will provide enough guidance for each of them to stay in their own designated areas. The one-way cycle track is to be 5 feet wide in order to provide ample room for a single biker to ride and room for passing when needed. Next to the cycle track will be a 2.5 foot pavement buffer with a curb that drops down to street level. This buffer provides room for bikers to avoid open car doors and prevent “dooring” accidents. The recommended distance for the door zone is 3 feet, but since the bikers are next to the passenger side of the car and the cycle track gives them plenty of room to go around an open door, this is not expected to be a problem. Next to the cycle track and curb buffer will be a lane of parking, providing vertical separation and acting as an impenetrable barrier between motor vehicle traffic and cyclists.

The parking lane was reduced from 8 feet to 7 feet, as a 7 foot parking lane can still accommodate the majority of personal vehicles and will encourage drivers to park as close to the curb as possible. In a study done in Cambridge, it was proven that as the width of a parking lane increases, so does the average offset between the curb and the car’s back tire. Next, there will be an 11 foot travel lane in each direction for motor vehicles. Although 11 feet is wider than typically needed, MassDOT recommends giving the extra foot to the travel lane when there is frequent bus traffic. Between the two travel lanes, there will be a 9 foot cobblestone median. The median not only allows for a left turn lane at intersections, but also provides space for emergency vehicles to pass (there is a fire station on this stretch of Centre Street) and for delivery trucks to be passed when they are pulled over. The median also provides an area for pedestrians to wait between lanes when crossing the street. With this design, pedestrians will only need to cross a single lane at a time and will have a place to stand when waiting for the next lane to be clear. This eliminates the multiple threat risk when crossing the street and makes it so that pedestrians can cross safely, without imposing stress.

Figure 3 – Current (top) and proposed (bottom) typical cross sections of Centre Street

Driveway/Low Volume T-intersection

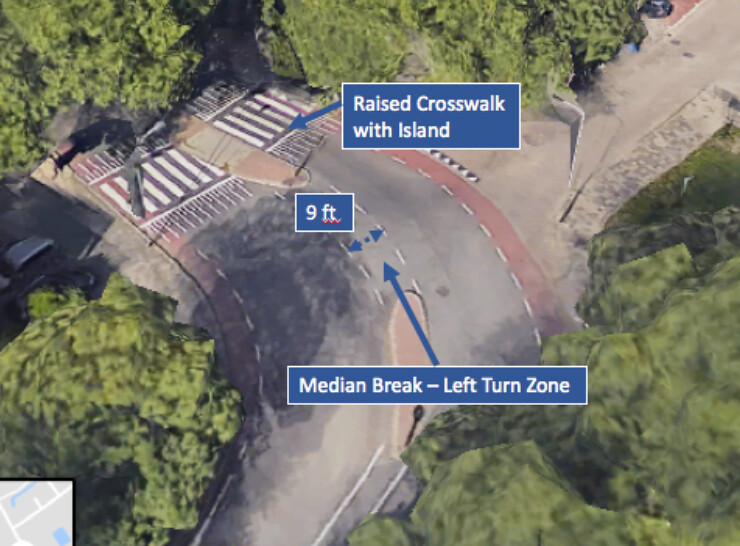

Along with the numerous official side streets intersecting Centre Street, there are a number of driveways to stores and parking lots that need attention (Figure 4). First, cutting the cobblestone median will allow for left turning cars to wait in the queuing space until oncoming traffic is clear. This will also allow for vehicles exiting the driveway to cross to the far lane. Next, the parking lane near the driveway will end and bump out with a raised curb (Figure 5, 6), improving visibility for cars leaving the driveway. Finally, a raised crosswalk will help slow drivers, creating a safer intersection with the prioritized cyclist and pedestrian traffic.

Figure 4 – A typical entrance to a driveway on Centre Street

Figure 5 – A Dutch example of a typical entrance to a low volume side street, which had a similar flow to that of a driveway

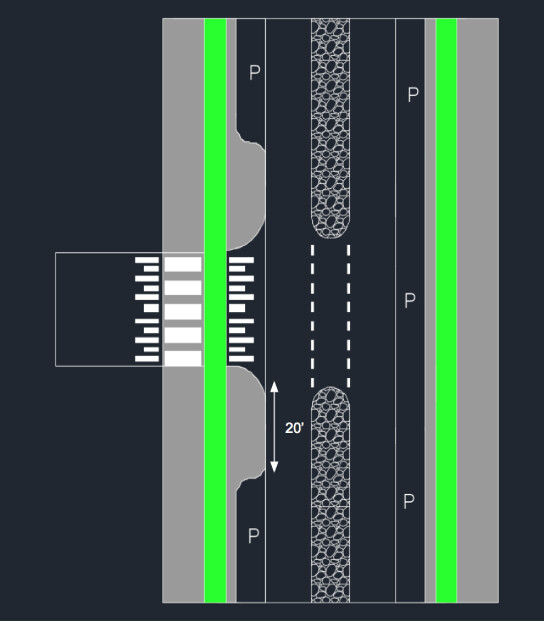

Figure 6 – Proposed design for a low volume side street entrance. Alternating short and long lines on either side of the crossing signalize that it is raised

T-intersection

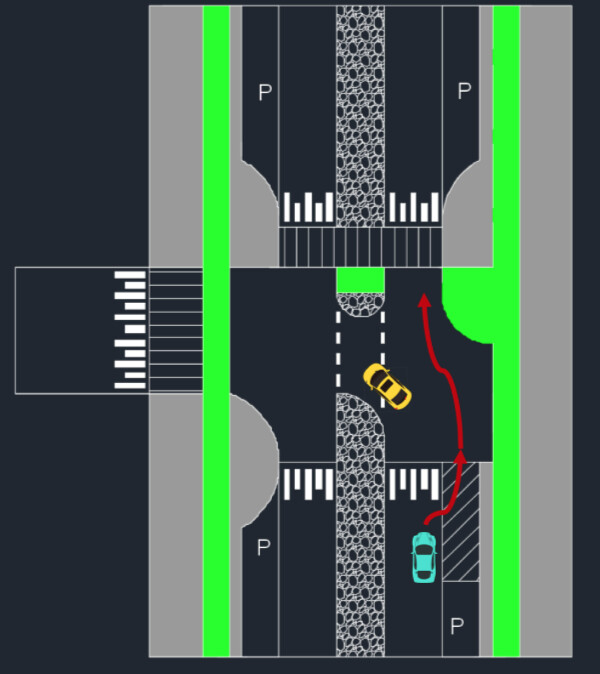

In order to remove the signalization in the currently signalized T-intersections on Centre St. (Figure 7), a few elements need to be added onto the the design in Figure 6 showing the driveway. First, the entire intersection will be raised in order to slow incoming drivers and create safer pedestrian and cyclist crossings. The piano key markings (Figure 9) signalize a raised intersection. To further increase safety, crossing islands will be used so pedestrians and cyclists only need to cross one lane of traffic at a time, removing the risk of a multiple threat collision (Figure 8). In addition, no parking will be allowed in or near the intersection to improve visibility for drivers. This also makes room for a bump-out queuing area, providing space for waiting cyclists and pedestrians and also minimizing the distance needed to cross in order to reach the other side. The empty space created in the parking lane also act as an informal flare, allowing vehicles to pass other vehicles that are waiting to turn left and improving the capacity of road.

Figure 7 – Current mid-volume T-intersection on Centre Street

Figure 8 – Dutch example of a T-intersection

Figure 9 – Proposed design of a T-intersection

4-way Unsignalized (2-way Stop)

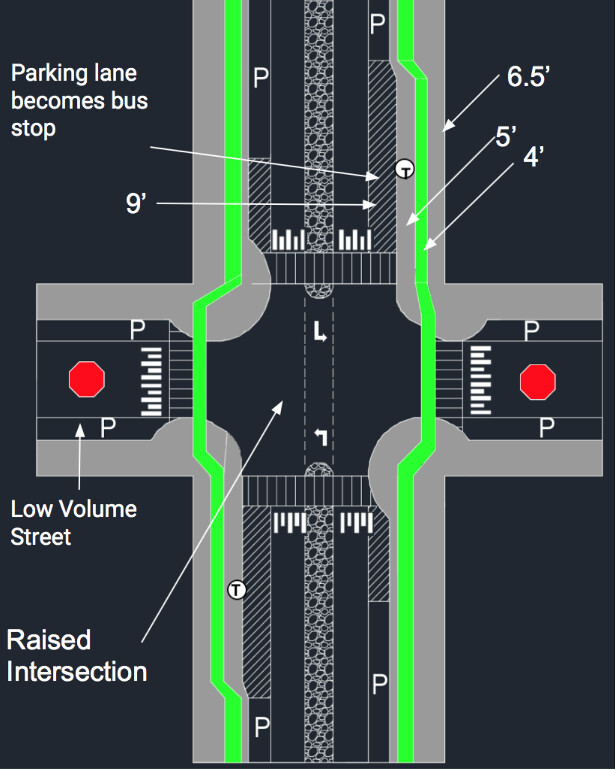

Four-way unsignalized intersections build on the design of the t-intersection with a number of different features. As is the case for t-intersections, the intersection will be raised to slow down the speeds of cars. In addition, crossing islands will be added to Centre Street so that pedestrians and cyclists only need to cross one lane of traffic at a time (Figure 11), rather than four lanes all at once as it is now (FIgure 10). To avoid collisions, vehicles on the streets that intersect with Centre Street will be forced the stop before entering the intersection due to the presence of a stop sign. Some of the four-way intersections also include bus stops, in which case the parking lane widens to 9 feet immediately after the intersection so the bus can pull in as close to the curb as possible. This means that the cycle track must narrow to 4 feet and move where the trees and street lights normally are and the overall sidewalk width narrows to 6.5 feet. A 5 foot bus stop island will be installed in the extra space, allowing pedestrians to wait there instead of having to cross the cycle track once the bus arrives (Figure 12). All four pedestrian crossings will be marked with zebra stripes, giving priority to pedestrians since there is no traffic signal to control who has the right of way. The combination of the curb bumping out and the cycle track being moved to the right forces right turning cars to intersect the cycle track at a 90 degree angle, providing the best possible view of oncoming cyclists. The bumped out curb also minimizes the distance that pedestrians need to cross, increasing overall pedestrian safety.

Figure 10 – An example of an unsignalized 4-way intersection on Centre Street

Figure 11 – A Dutch example of a 4-way unsignalized (2-way stop) intersection

Figure 12 – Proposed design for 4-way unsignalized (2-way stop) intersection

4-way Signalized

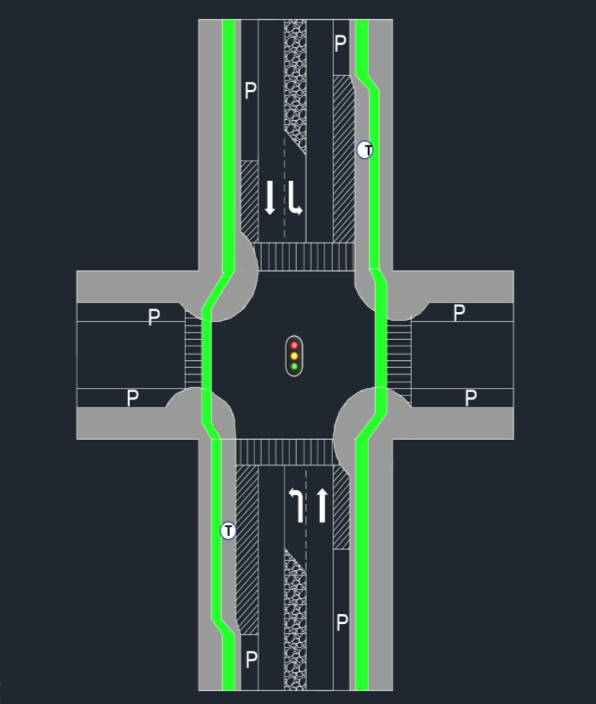

At high volume intersections where the LOS is C, such as those with LaGrange, Corey, and Belgrade (Figure 13), traffic signals are needed. We designed the left turn lane to take the place of the stone median allowing cars to queue without blocking through traffic (Figure 14, 15). At signalized intersections, crossings for cyclists and pedestrians can be signalized and synced up with the phasing of the motor vehicles in order to create a safer environment for crossing. The right turn design is the same as the unsignalized intersection, as right turns made on a green light will still be yielding for a bicyclist and/or pedestrian with their own green light.

Figure 13 – A current signalized intersection on Centre St.

Figure 14 – A Dutch example of a 4-way signalized intersection

Figure 15 – Proposed design for a 4-way signalized intersection

Conclusion/Reflections

Table 1 – Conclusion of design features for each intersection

| Type of Intersection | Driveway | T-intersection | Unsignalized | Signalized |

| Volume of Intersecting Road Traffic | Low | Medium | Medium | High |

| Features of Redesign | Raised crosswalk, curb bump-out | Raised intersection, bump-out, informal flare, crossing island, bike queuing zone | Raised intersection,

bump-out, crossing island, bus stop |

Bump-out, bus stop, left turn lane, signalized crossing |

Any sort of project development and completion brings with it a slew of lessons learned for those involved. In the case of the Centre Street redesign, our team highlighted a number of methods and principles that we find to be the most worthwhile to consider when performing a similar task in the future. In the specific case of a complete streets design, pedestrian safety is the top priority and is primarily achieved by slowing traffic. While adding bike infrastructure and increasing greenery is undoubtedly desirable, designers must be focused first and foremost on slowing down the vehicular traffic. It can be easy to lose sight of the main objectives of a street design given the many pieces involved, but our team now sees the importance of identifying the primary goal and tailoring the design around that.

When proposing a new project that requires funding and construction, perhaps just as vital as the actual design is the way in which it is presented to the relevant audience. The Centre Street redesign is heavily tied to outside opinion, as the City of Boston would not proceed with the project unless it benefits the public. As a result, our team had to focus on how to convince our audience that our design was desirable without mentioning esoteric engineering principles. Though the ability to give effective presentations comes with practice, we made sure to explain concepts such as why a 2+2 to 1+1 roadway reduction would not cause traffic jams and exactly how pedestrians would be safer in terms that any member of society would understand. Faculty and other reviews imply that we still have work to do in this regard but we now have some specific areas to work on for next time.

Our last revelation regarding the street design itself was the importance that minute details have in the overall picture. When designing with a complete streets mindset, it is easy to quickly jump to the addition of bike infrastructure and narrower travel lanes but everything falls apart if the subtleties are not considered. For example, a narrow roadway is great for slowing traffic but what happens when traffic is heavy and an emergency vehicle needs to get through? Having a bus stop island for pedestrians is an effective safety feature, but if it is it not wide enough to be ADA compliant then it is essentially useless. Every inch of our allotted roadway space needs to be carefully considered to ensure that the whole system works in harmony. Though some design features may be very attractive, if they negatively affect another component then more adjustments need to be made or the idea needs to be rejected altogether. Traffic design is a balancing act that trickles down to the finest details.