Sammy Alshawabkeh| Alex Bender| Kevin Carr|Yuhao Gu|Alex Trzaskowski

Background

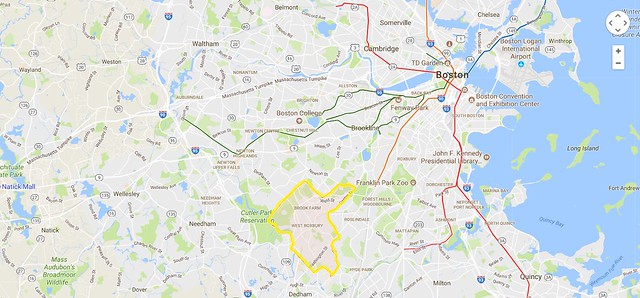

West Roxbury is an outlying, mainly residential neighborhood in the southwest corner of Boston, situated about 12 miles from downtown. As shown in Figure 1, it lacks direct connections to the MBTA’s rapid transit system, although several bus routes run through the area. The only direct connection between West Roxbury and Downtown Boston is the Needham Line commuter rail, which has three stops in the neighborhood, and runs every one to two hours in each direction. Because of the lack of transit serving the community, is has become the most auto-dependent neighborhood in the city. According to the Go Boston 2030 Vision and Action Plan, published by the City of Boston in 2017, 70.4% of West Roxbury residents drive to work, compared to the 40.6% citywide average. Conversely, only 14.5% of West Roxbury residents take public transit to work, against the 33.0% citywide average. The neighborhood contains a large vulnerable population, and features dozens of schools, health centers, and senior centers, largely centered around the community’s principal streets and avenues.

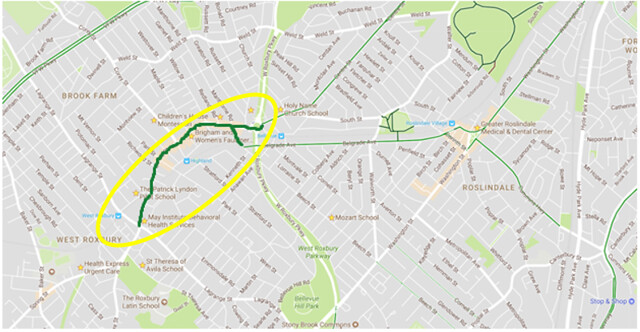

Figure 1. West Roxbury, highlighted in a map of the city of Boston and neighboring communities. Note the highlighted MBTA transit lines, which do not serve West Roxbury.

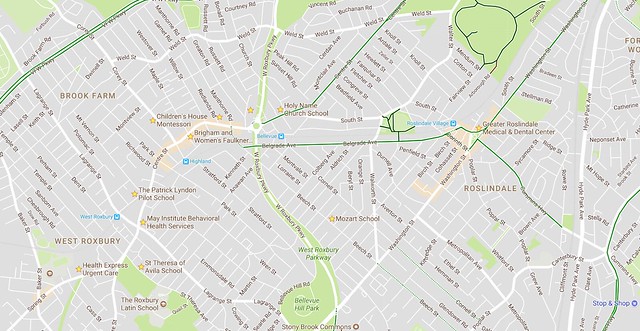

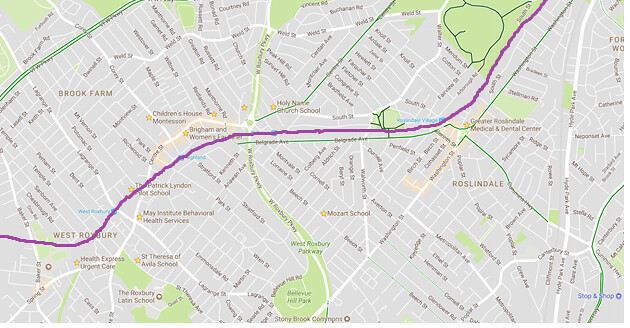

The main street of West Roxbury is Centre Street, which is the only street in the neighborhood with significant commercial activity. It is a mixed-use corridor that functions as a neighborhood principal, connecting the dozens of residential cross streets to one another, and links West Roxbury to Roslindale and Jamaica Plain to the North, and Dedham to the South. Because it carries some through traffic between communities, while carrying significant local traffic, it can be classified as a grey road and is the primary mixed-use corridor in the community. It is also a transit node, as four MBTA bus routes are partly located there, and the previously mentioned MBTA Needham Line runs parallel to the street in the neighborhood. Despite being a major road for cars and transit, however, the street is currently unfriendly to bikes, and features no bicycle infrastructure. Figure 2 shows a more detailed map of West Roxbury, highlighting major points of interest in the community, as well as existing nearby bicycle routes (highlighted in green). The stretch of Centre Street in Roslindale and Belgrade Avenue currently has bike lanes which could take cyclists from West Roxbury to Brookline and Forest Hills, respectively, but bicycle facilities along Centre Street in West Roxbury are lacking to complete the connection.

Figure 2. Centre Street in West Roxbury, highlighting existing bike facilities and major points of interest.

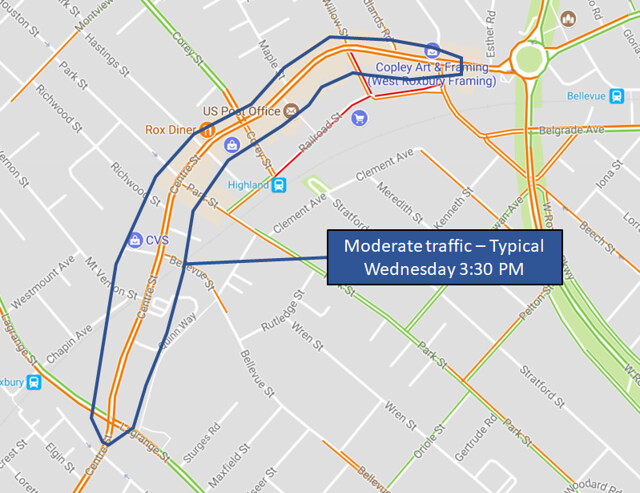

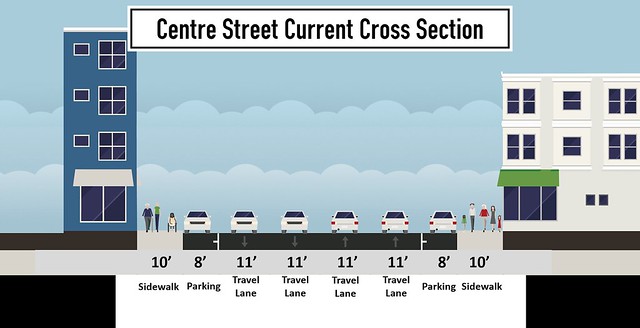

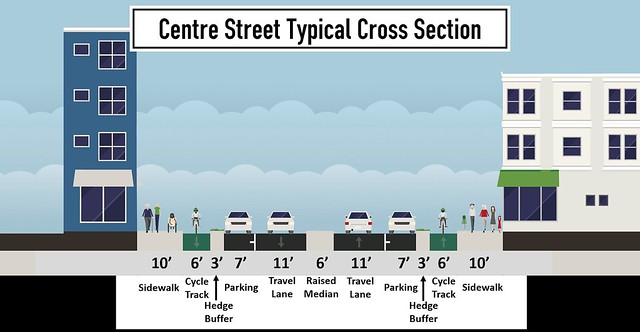

This design will focus on the segment of Centre Street between Lagrange Street and Belgrade Avenue, which is about 0.7 miles long. The route under consideration typically experiences patches of moderate to heavy traffic in the morning beginning around 9:30 AM, then sustained moderate to heavy traffic in the afternoon from 2:30 – 7:00 PM, according to Google’s traffic tool (Figure 3). Once a two lane (1+1) road, Centre Street was widened to its current state in 1972, and since then has had two lanes of traffic moving in each direction (2+2) (Figure 4). This was likely due to a reactionary traffic policy in the city of Boston which required wide lanes and multi-lane roads wherever possible, due to fears that the road network in 1960s Boston could not adequately contain traffic. The direct catalyst for such a policy could have been Governor Francis W. Sargent’s moratorium on freeway construction inside of the Route 128 corridor, which sought to conserve Boston’s cityscape, neighborhoods, and green space, but also went against the increasing trend of car ownership in the United States. Much as in the design of major highways, increasing the capacity of arterial roads in American cities has usually induced traffic as opposed to reducing it, as a wider street appears to a driver to be a faster option, and invites enough additional through traffic to become as congested as it was before its widening.

Figure 3. Google Traffic map showing typical traffic along Centre St. on Wednesday at 3:30pm

In addition to not solving traffic problems, the widening of a street like Centre Street can create unforeseen safety and accessibility issues, and it is these issues which the design seeks to correct.

Figure 4. Current typical cross section of Centre St.

Santa’s Delfts has been tasked with proposing a redesign for the stretch of Centre Street from Lagrange St. to Belgrade Ave. The design must keep the curbs where they currently are, giving the street a consistent 60 foot cross section, with 10 foot sidewalks extending on either side.

Reason for Action

The current state of Centre St. in West Roxbury is not ideal given construction ability, traffic volume, and neighborhood context. The road is seen by many as a sewer for traffic because of the unattractive look and the flow of fast moving cars (in off-peak hours) and largely stop & go cars (in peak hours). The area surrounding this stretch of Centre Street is home to an abundance of middle-class communities. There are numerous schools, residences, and shops nearby; the street seems to contradict the quiet atmosphere of much of West Roxbury. This contradiction stems from many places such as the lack of cyclist and pedestrian friendliness (Figures 5 and 6).

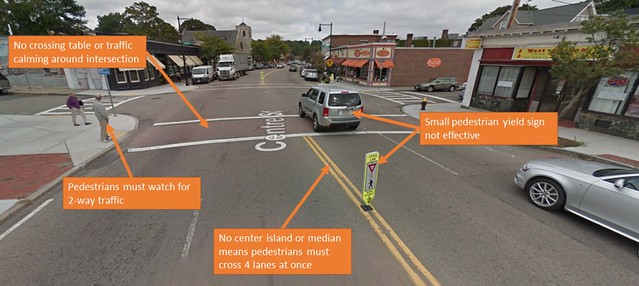

A major issue with this stretch of Centre Street is pedestrian safety at crosswalks. Pedestrian accidents have occurred, including one in 2015 which resulted the victim’s hospitalization. There are stretches of Centre St. that require pedestrians to cross 2 + 2, fast moving traffic. The small “Yield to Pedestrians” sign and the zebra crosswalk are inadequate. No median exists between the two-way traffic, so crossing at a non-signalized intersection can be dangerous (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Current unsignalized intersection of Centre St. at Hastings St.

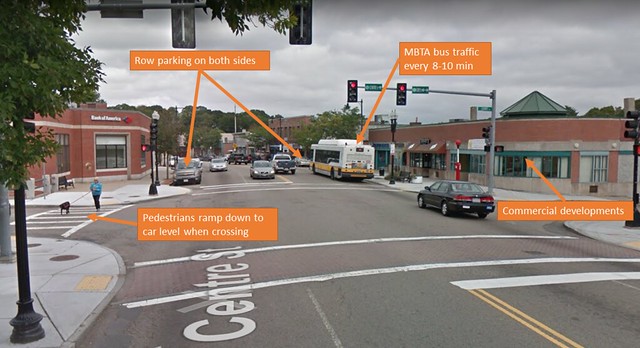

Figure 6. Current signalized intersection of Centre St. at Cory St.

The Dutch consider crossing four lanes of traffic at once to be inhumane and unimaginable. When a pedestrian does not feel safe crossing four lanes of traffic, they must go far out of their way to reach a signalized intersection in most cases . This lack of pedestrian friendliness is not in accordance with principles of systematic safety (which are Speed Control & Separation, Forgiveness & Restrictiveness, and Predictability & Simplicity), which provides a huge impetus for redesign.

Also, due to the lack of bicycle facilities on the street, the current state of bicycle travel on this stretch of road is dangerous. Cyclists are expected to act as a vehicle on a stretch of road with a huge vehicle speed differential, potential for passing, and wide lanes. It is not uncommon for a cyclist to be passed by a zooming car on this road (even sometimes on both sides, such as when a left turn lane appears). For cars and bikes to safely be in mixed traffic, the speed of cars must be below 25 miles per hour, which is much lower than Centre Street’s actual current state. Because of imperfect street design, cars move much faster than they should on this road. Traffic calming measures have not been designed into the road to self-enforce speed limits. The 2 + 2 road enables passing, which is an incubator for speeding. The lack of self-enforcing traffic calming is another integral impetus for a redesign. Finally, the current state of this stretch of road is not well connected to rapid transit and bicycle networks (Figures 1 and 2). Centre St. is plagued by high bus traffic (one every 8-10 minutes). This bus traffic aides in increasing pollution, driver delay, and the unattractiveness of this stretch. The parallel commuter rail line is highly underutilized, largely because of the constraints an infrequent commuter rail creates. There are decent bicycle facilities nearby this stretch of Centre Street, but are disjointed due to the interruption posed by this stretch’s lack of safe bicycle facilities.

Vision & Design Objectives

The ideal design addresses all of the major problems currently existing. The design intends to address pedestrian friendliness by enabling pedestrians to safely cross the road at almost any point. On a street flanked by shops on both sides, pedestrians tend to cross anywhere, and thus need a high number of safe crossing locations. This is achieved in the design through calming traffic (lower speeds equate to higher comfort and safety for pedestrians) and ensuring pedestrians are only crossing one lane at a time by establishing an unmountable median and crossing islands. The design hopes to address the current lack of safety by drawing on many principles of systematic safety, such as ensuring all traffic calming measures are self-enforcing, so drivers have no choice but to go the speed limit.

The design places a large emphasis on the beautification of this stretch of road. Centre Street can be a road the community is proud of and one that everyone has a good, safe experience on. Having an attractive road will also be good for economic development (as shown by popular streets such as Newbury and Boylston in Boston). Local businesses suffer when people are not as likely to spend time in the area and shop around, so it is in a business’ best interest to support this redesign. The design envisions very green stretches of road as well as attractive bicycle facilities. Bike travel will be encouraged and promoted on the new Centre Street by providing safe, attractive bicycle amenities.

On a grander scale, the root goal of the design is to promote a “Car Lite” neighborhood. By increasing bicycle accessibility/safety and rapid transit accessibility/frequency, the community of West Roxbury can be well on their way to being a sustainable model for the rest of Boston. The design improves overall access to the rest of the city, while decreasing current car reliance. This Centre Street redesign will be forward thinking and a great solution to the current drawbacks of the road.

As previously mentioned, the MBTA runs four bus routes down Centre Street (the 35, 36, 37, and 38), which connect West Roxbury residents to Forest Hills station, the current southern terminus of the Orange Line. According to the MBTA Ridership and Service Statistics, these buses collectively carry 8,359 passengers every weekday on average, down a corridor that runs roughly parallel to the MBTA Needham Line for the length of street which is being redesigned.

In the next few decades, a major push is being made by the City of Boston to move toward Diesel Multiple Unit (DMU) engines for commuter rail trains, which allow for quicker acceleration and deceleration at stops and can be run at a similar frequency to rapid transit. These will be piloted on commuter rail lines which are closer to the city center, like the entirety of the Fairmount Line, and the stops of the Framingham/Worcester line in Newton, by 2024. Because the Needham Line, and particularly its stops in West Roxbury and Roslindale, does not extend very far beyond downtown Boston, it would be another worthy candidate for this upgrade. As a DMU train, the Needham Line could run every 15-20 minutes in both directions, and may carry any passengers who needed a bus connection to Forest Hills and to the MBTA rapid transit system. This increase in rapid transit will enable a decrease in bus travel on Centre Street (1-2 per hour), helping to decrease backups and make the road more attractive. This concept is an imperative part of our design, and would support the increase in multimodal transit induced by a streetscape which promotes walkability and bikeability.

Proposed Typical Cross Section

Figure 7. Proposed typical cross section of Centre St., with two-sided parking

Figure 8. Dutch inspiration for typical cross section

https://flic.kr/p/WJemvp

The typical cross section of the new design for Centre Street will span over the entire section length, excluding intersections. Typically, there is about 60 feet curb to curb. The focus of the design is to improve bicycle functionality and intersection safety, while maintaining facilities for local traffic. The road will be converted from a 2+2 travel lane, to a 1+1 (Figure 7). The design will typically consist of cycle tracks, parking, travel lanes, and a median.

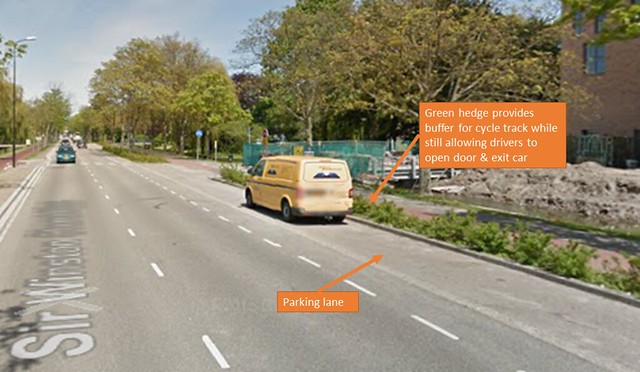

The inspiration for the new design of Centre Street stems from the road design of Kristalweg in Delft. Kristalweg is an existing 1+1 road that is narrow and contains a center median between its travel lanes. The parking lane is distinguishable from the travel lane by using a brick surface. A vertical separation between the parking lane and the cycling lane is provided, to ensure safety on the cyclist. There are little to none conflicts between vehicles and bicycles on this road. (Figure 8).

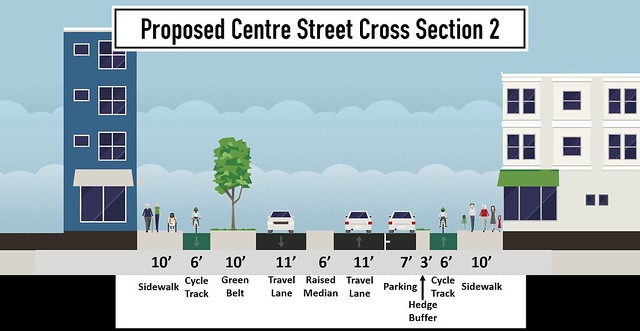

We will propose strategically removing parking on one side of the street (subject to community deliberation) in specific areas to improve the functionality of the cycle and travel lanes, as well as to improve the aesthetic of the road (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Proposed typical cross-section of Centre St., with one-sided parking

The proposed cycle track is 6 feet wide, on both sides of the street. We are allocating 6 feet for a one-way cycle track to provide adequate space and comfort to the cyclist. A wider cycle track also provides enough space to allow friends to cycle together. A 3-foot buffer zone will be provided to separate cycle tracks from adjacent parking lanes. We justified 3 feet for the buffer to ensure safety to the cyclist if a car door opens along the parking lane. The buffer will be a green hedge strip to provide a physical separation between the cycle track and the parking, as well as improve the aesthetic of the street.

The buffer provided in our design is a hedge buffer, inspired by the design on Sir Winston Churchilllaan in Rijswijk. The hedge buffer provides a green separation between the parking lane and the cycle track, while still providing enough space for the passenger to exit the vehicle. The buffer is at a height that will not interfere with the door of the parked vehicle when opened (Figure 10).

Figure 10. Dutch example of green hedge next to parking

The length of the travel lanes will be 11 feet wide, next to a 7 foot wide parking lane. Having a narrow parking and a narrow travel lane does not work well because it does not allow enough space for a motorist to safely parallel park without brushing the median. It also does not allow enough space for the motorist to safely exit their vehicle against oncoming traffic.

Pedestrians constantly cross the street without using the crosswalks, since it is a commercial area. We want to provide safety for the pedestrians to cross the street without having to sprint across it. The major purpose of our median is to have a forgiving design, in accordance with the “forgivingness” principle of systematic safety. We know, especially in Boston, that people will jaywalk, so the design still makes it impossible to cross multiple lanes at any one time. The proposed design will provide a median also to channelize traffic. The median is 6 feet wide in order to provide safety for crossing pedestrians, as mentioned earlier. The median will be raised to be unmountable (rough cobble), preventing cars from driving on it, yet pedestrians will be unbothered.

Key Design Details and Justification

In order to ensure a design that met all of our objectives, we sought to emulate Dutch design elements as closely as possible, and as appropriately as the intersection would allow. For points in our design that deviated from the typical cross section, we had to modify our geometry, signaling, and right-of-way prioritization to fit a given situation. As this stretch of Centre Street is relatively uniform, the two main deviations that we designed for were a signalized intersection and an unsignalized intersection.

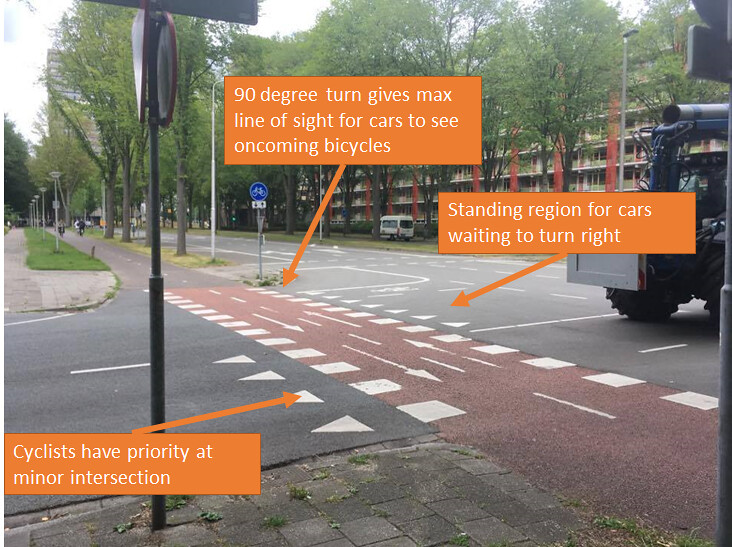

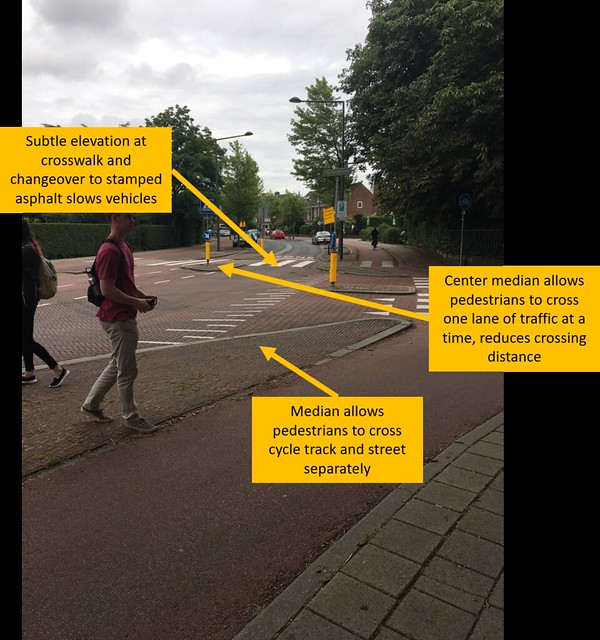

Figure 11. Dutch inspiration for unsignalized intersection

Figure 11 shows Voorhofdreef in Delft, NL. This is the typical Dutch intersection where a major road intersects with a minor one. The intersection is unsignalized and bikes are given priority. Space is assigned for the turning vehicles when they’re yielding to cyclists to avoid blocking traffic. With striping and other forms of guidance the route of turning vehicles is designed to intersect with bikes at a right angle, this ensures the maximum mutual visibility between people in cars and on bikes.

Figure 12. Dutch inspiration for signalized intersection

Figure 12 is taken from Papsouwselaan in Delft. This is a signalized intersection with a decent amount of through and turning traffic. The width of the street would be too wide for pedestrians to cross all of its lanes at the same time, so the median is extended to act as a safety island, which prevents pedestrians from having to cross more than two lanes at once. This also means pedestrians don’t have to watch for traffic from both directions at the same time.

Road Diet, Bump Outs, and Crossing Tables

The principal features of our design are purposefully complementary. Because the perceived safety and actual safety of bicyclists and pedestrians on a street are closely linked, narrowing Centre Street in order to calm traffic would not only cut down the number of automobile-related deaths on the street, but would encourage residents to walk or bike in the neighborhood more often. Currently, the largest threats to pedestrian and cyclist safety on this street are speeding and limited visibility due to the road’s width. Both of these items can be addressed by narrowing a road, or implementing a “road diet.”

As seen in Figure 5, double parking does occur on this stretch of road, and not only for deliveries. Double parking is a sure sign of extra capacity, proving our justification for this proposed road diet.

In this proposal, the design calls for narrowing a street which currently carries two lanes of traffic in each direction and converting it to a street which carries one lane of traffic in each direction. Drivers are more likely to feel constrained by the road’s design if they are forced to follow the speed of the driver ahead of them, instead of being able to move between lanes in pursuit of an open stretch of road ahead of them. However, this does not solve the speeding issue on its own: In order for such a design to be successful in keeping drivers at the speed limit, which in this case is twenty-five miles per hour, drivers must not be in an environment that encourages speeding because of any geometric or physical cues.

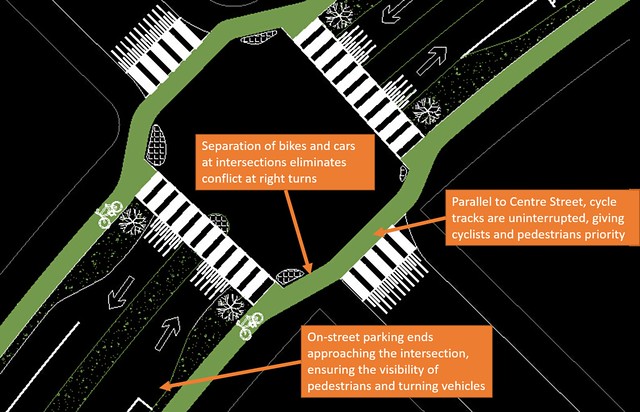

The “road diet” addresses the second safety concern of limited visibility by keeping the road narrow, and thus narrowing crosswalks. It is an unfortunately common occurrence for pedestrians to be killed in what is called a “mercy killing” or “double jeopardy situation”, whereby the pedestrian who has priority is signaled by a driver in the first lane to walk, only to be hit by an unaware, speeding driver in the second lane, who could not see that pedestrian. The lane reduction in this fashion reduces the potential number of conflicts between pedestrians and cars at unsignalized intersections, of which there are several in the existing conditions. Additionally, visibility by both pedestrians and cars should be maximized by eliminating a few on-street parking spots on each side of the street as Centre Street approaches an intersection. Where the street widens at an intersection to accommodate turn lanes, pedestrians should have safety islands (Figure 13) in the middle of the street, so they only have to decide to cross one direction of traffic at once. The former bump outs are maintained or widened to help channelize the traffic as well as providing pedestrians a crosswalk which is easier to cross.

Figure 13. Plan view of proposed signalized intersection (west leg)

Figure 14. Plan view of proposed signalized intersection (east leg)

Figure 15. Plan view of proposed unsignalized intersection

In this case, Centre Street cannot have excessively wide travel lanes, will provide frequent bumped-out pedestrian crossings (causing driver “S-curves”), and should contain periodic crossing tables. These elements will keep drivers vigilant and aware of their speed, in some cases by physically making it impossible for them to drive safely at a higher speed. Finally, within the area of these intersections, the pavement treatment will change in order to tell drivers that they are entering a different zone. This change, then, will make them more aware and cautious. A similar treatment can be seen on Ruys de Beerenbrouckstraat in Delft (Figure 16). This street is a prime example of how to design for a specific speed rather than relying on posted speed limits. The street uses raised crossing tables and different pavement treatments (i.e. stamped asphalt at pedestrian crossings) to force vehicles to slow down and create a “new room” effect, where drivers are alerted of entering a pedestrian area by its unique properties.

Figure 16. Key principles displayed at Ruys de Beerenbrouckstraat

In accordance with the Dutch “skinny roads, wide nodes” principle, our narrowed design will still have enough capacity and throughput through intersections. This is done primarily by ensuring the design has left turn lanes where necessary. In the current state of Centre street, the lack of dedicated left turn lanes can effectively make the road 1+1 anyway since the leftmost lane can be blocked by left turning cars. This further proves that the current traffic capacity can still be carried through the proposed road diet. Finally, in the proposed design, all left turn lanes will be in line with each other, maximizing drivers’ line of sight toward oncoming traffic (Figures 13 and 14).

Cycle Tracks

Having a cycle track on Centre Street will mitigate the lack of bike safety currently on that street by reducing conflict both at intersections and on the street itself. By implementing cycle tracks, cyclists will no longer have to worry about being passed or hit by an approaching car that is travelling faster than they are. At minor intersections, bicycles will have priority over cars so that drivers have to watch for approaching cyclists in order to make turns, and this will be reinforced by the inclusion of crossing tables at these intersections (Figure 15). Crossing tables will make it so that cyclists going straight down the street will not have their travel interrupted, and that cars will have to rise up to the level of bikes in order to make a turn, forcing them to approach the crossing more cautiously.

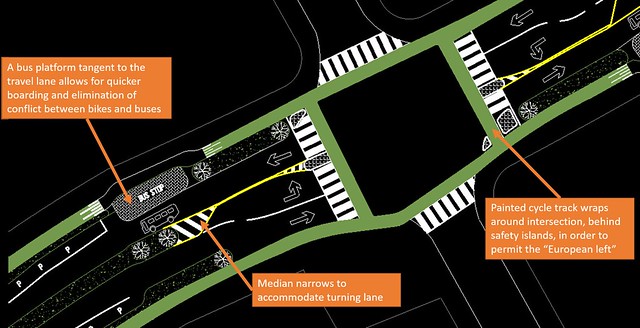

Major intersections will be signalized, and this includes signals for those riding in the cycle tracks. As a driver approaches the intersection, the median will become narrow enough to become a turning lane. Parking will be removed along the intersection, and will be replaced with either a bus platform tangent to the travel lane or be replaced with tree foliage. At the bus platforms, cycle tracks will need to be level with the sidewalk to provide accessibility for wheelchair users. At these intersections, cyclists stop ahead of cars to provide a line of sight for drivers to acknowledge the cyclists and slow down speed. The cycle track will be painted around the entire intersection, behind safety islands, in order to permit the “European left,” a Dutch design concept (Figure 17).

Figure 17. Dutch design concept for four-way signalized intersection

Pedestrian safety islands between cyclists and drivers, and bike stop lines which are farther into the intersection than those for cars, will make bicyclists more visible as they maneuver through the intersection. Additionally, a cycle track ensures that bikes are never expected to share a lane with buses, including at bus stops. At these stops, buses will not pull into the curb, but will stay in the travel lane, and pedestrians will board at a pedestrian island, which the cycle track will pass behind. This completely insulates cycle traffic from motorized traffic, while minimizing bicycle-pedestrian conflict.

The design provides for a cycle track immediately adjacent to the curb, as opposed to the on-street parking which is currently there. This adds perceived width to the sidewalk, which is appealing not only to residents, but to local businesspeople who could benefit from outdoor seating and increased foot traffic in front of their establishment. The cycle track will be at an intermediate level between street and sidewalk.

Street Function

The outlined safety vision for Centre Street, implemented using the above techniques, operates in tandem with the design’s goal for the street’s function. Currently, the peak hour traffic suggests that this road is often used as a through road, in which neither the motorist’s origin or destination is on the street. Traffic calming efforts will not only improve safety, but will reinforce Centre Street’s status as a neighborhood principal by ensuring that it is only appealing to local drivers. In West Roxbury, the VFW Highway, to the north of Centre Street, carries traffic from Dedham to the Jamaica Plain neighborhood of Boston, which is well connected to the rest of the city via several other parkways. To the south of Centre Street, the West Roxbury Parkway carries traffic through West Roxbury from Roslindale to Hyde Park, which is well connected to Dorchester, Mattapan, and Milton through local parkways and collector roads. Since it is clear that drivers in the area have other options for travelling longer distances, reducing Centre Street to one lane in each direction, accommodating cyclists, and appropriately calming traffic would make the street lose its “grey road” character by redirecting through traffic via local highways and only encouraging local activity.

Bike Network Connectivity

While this design seeks to clarify and build on the strengths of Centre Street by essentially demoting it to a lower-traffic street, it also seeks to connect bikers to the greater bike network in Boston. In order for Centre Street to function as a carrier of multimodal traffic, bicyclists need their cycle track to meaningfully connect them with existing bicycle infrastructure. Centre Street is actually the main street of a few other neighborhoods, namely Roslindale and Jamaica Plain, and in those areas, it generally has single lane automobile traffic with bike lanes. By creating a cycle track along the segment of Centre Street running through West Roxbury, cyclists become connected to neighboring communities, as well as to rapid transit via the Orange Line. Some other nearby streets which provide bicycle facilities are the VFW Parkway and the Arborway, which would connect cyclists to the Emerald Necklace, some of the northern neighborhoods of Boston, and to the Chestnut Hill area (Figure 18).

Figure 18. Proposed bike network with connectivity to existing network

Beautification

According to our vision, we would like Centre Street to be safer and more appealing to pedestrians and bicyclists, not only because safety in the public realm is what all streets should be designed for, but also because Centre Street is the main street of West Roxbury and needs to carry out the functions expected of an urban main street. In addition, this focal point of the community lacks aesthetic appeal, mainly due to the width of its road that is dedicated for cars, the off-street parking that dominates blocks of property off of the right of way, large suburban-style shopping parcels, and a lack of trees or hedges. The proposed design includes a number of elements which address these issues.

A tree-lined green space which could be added in place of on-street parking in certain areas along the street will create a canopy effect, making it more pleasant to walk in the warmer months and providing pedestrians, cyclists, and residents a barrier from the noise and air pollution generated by car travel. While this could be met with some resistance from the community, we would like to show an example of what this could look like and let the community decide their desire for parking/green spaces (Figure 9). We believe some reduction of parking in certain areas is justified because it will not likely decrease the neighborhood’s parking capacity, as many spots are often left unfilled, and there is a large amount of off-street parking for the larger businesses nearby. Thus, replacing some of the existing two-sided parking with a green space on one side should have no negative effect on the experience of motorists in the area, while beautifying the area for pedestrians and cyclists, and making the street a more appealing public space.

As we know, the best way to show that something can be done, is to show that it has been done. Our design, in tandem with GoBoston’s 2030 vision for the city, can prove the benefits of scarcely placing on street parking. Officials in Roslindale (another Boston neighborhood) have been exploring the idea of removing on street parking on Washington street, and striking a deal with private parking lot owners to meter parking spaces in lots nearby old on street parking. A similar concept could be implemented on the stretch of Centre street. The city can partner with the private sector to foster a symbiotic relationship that benefits cars users, the city, the private developers, business owners, and most importantly the community. We as Americans can step away from our rigidity of mindset; we can loosen our grasp on maintaining parking spaces.

Public Transit Accessibility

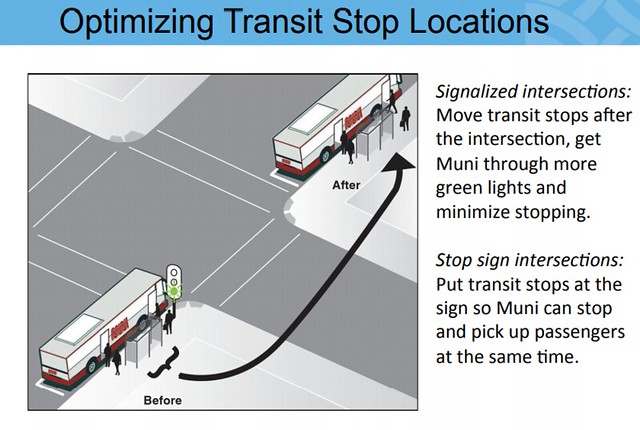

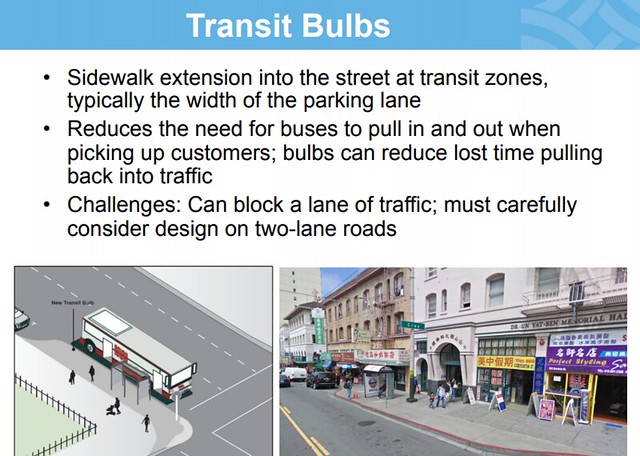

Centre Street’s prominence in the community makes it a logical candidate for Complete Streets design principles, meaning that the street should be accessible to all forms of transportation and should be connected with the rest of the city in a meaningful way. As previously mentioned, our design was based on the assumption that the Needham Line increasing its service could supplant some of the service provided by the existing bus routes, cutting bus frequency in half. This will also help to decrease car traffic in the area. This is desired because rapid transit is more sustainable, and with a 1+1 road design, frequent bus stops would cause frequent road blockages. Near intersections, since the parking lanes/green spaces will not continue, cars will be able to pass buses’ brief stops so even the infrequent stopping won’t present a major blockage. This is a reasonable condition for what we have designed, but only if the current frequency of these bus routes is reduced. Backups will be very infrequent because bus frequency will be low, and the bus will not pull out into a bus bay, optimizing boarding time and minimizing car delay. Also, when designing for bus stops, in addition to Dutch principles on Ruys de Beerenbrouckstraat (bus should always stop in travel lane), we were inspired by Western San Francisco’s recent design concepts, which are summarized in Figures 19 & 20.

Figure 19

Figure 20

Figure 21. Current commuter rail network through West Roxbury

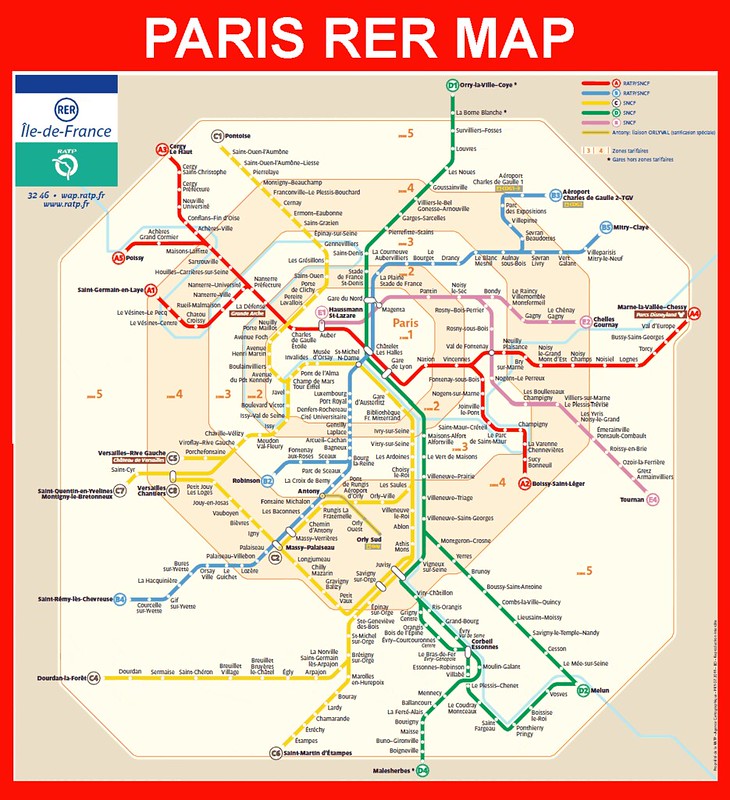

Because some of these routes run parallel to the rail right of way (at least on Centre Street) and run a similar course into Boston, some of these routes will become redundant with the introduction of rapid transit in the area (Figure 21). Some possibilities for this rapid transit service would include an extension of the Orange Line down its current right of way (as is planned for the Roslindale Village stop, slightly inbound from the project site) or RER-style (French commuter rail) service, whereby commuter rail stops with high frequency are directly linked to the rapid transit network (Figure 22). This same sort of commuter rail to light rail conversion can be seen in a proposed conversion in Rotterdam’s transit network to its North Harbor. Also, a similar conversion has already taken place on the Green Line’s D branch, which used to be a commuter rail line.

Figure 22. Map of Paris rail system

Reflections

Overall, our group worked very well together and we relied on each others’ various strengths. Every member was very critical of our design, causing us to do a lot of rethinking (for the better). Also, an imperative section of our group’s success stemmed from the notion of everyone having a voice. Our design was a very collaborative effort.

In our application of Dutch principles, we realized that Americans have a very rigid mindset when it comes to motor vehicle transportation. We have been able to combat this by explicitly showing examples of Dutch streets that are analogous to our design. Since progressive designs have been done in the past, there is no reason they cannot be done again. We want the city to consider our progressive design, from a forward-thinking viewpoint.

Unfortunately, we were not able to reduce the width of the travel lane due to the narrow parking lane. We would have preferred to reduce the width from 11 feet to 10 feet, and in some cases to 9 feet, but there is not enough space to accommodate a driver that is parallel parking next to an unmountable median. Another design modification that we would have been preferred is to apply roundabouts at some intersections to maximize safety (since roundabouts have been proven to be safer at many intersection types), however the space provided at intersections is not wide enough to implement this design, as drivers may simply drive over them. We considered the idea of providing parking on only one side of the street in certain locations, however that is a decision we want to involve the community in.

The changes that we were able to make allocated space once given to cars for multimodal transportation and recreational enjoyment. At the very least, our design provides for a safe environment for bicycles and pedestrians and for traffic calming principles which can change the character of the street. At most, we provide a framework for a more vital corridor in a more forward-thinking, transit oriented community that is attractive to its residents and well connected to its neighbors.

Assumptions

- Community helps to make decisions on parking/green space

- Rapid transit conversion

References

boston.gov. (2017). GoBoston 2030: Vision and Action Plan. [online] Available at: https://www.boston.gov/sites/default/files/document-file-03-2017/go_boston_2030_-_full_report_to_view.pdf [Accessed 14 Jul. 2017].

MBTA.com. (2017). Ridership and Service Statistics. [online] Available at: http://www.mbta.com/uploadedfiles/documents/2014%20BLUEBOOK%2014th%20Edition(1).pdf [Accessed 14 Jul. 2017].

nacto.org. (2017). Transit Stops & Stations: Stop spacing, location, & infrastructure. [online] Available at: https://nacto.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/1-7_Tanner-Transit-Stop-Spacing-Location-and-Infrastructure_2015.pdf [Accessed 14 Jul. 2017].