Team: Maggie, Katie B, Kim, Stephen

Cyclists and Pedestrians

When we visited Amsterdam as a class on Saturday we explored some areas where cyclists and pedestrians interacted to learn how as engineers we can create a safe environment for both. Cycling and walking are means of transportation that are especially suited for the area we visited. We observed two types of interactions: those with few cars and those with many cars. As a whole, the experience was chaotic with questionable safety at face value, but with a closer look we saw the spectacular human reaction and interaction when navigating the busy streets of Amsterdam on a Saturday afternoon.

The map above shows the various locations we visited. The red markers indicate the locations where there were few cars while the blue markers indicated where there were many cars.

With Few Cars

Spiegelgracht

Spiegelgracht is the name of the canal and the street we observed this past weekend. Interestingly, the canal is listed as one of UNESCO’s World Heritage Sites. Regardless of its heritage however, Spiegelgracht has adopted vehicular, cyclist, and pedestrian separation. The western side of the canal is a one way (northbound) street for vehicles and a one way cycle track. The eastern side of the canal is also one way (southbound) for vehicles with parking on the side, sidewalks on either side of the street, but no bicycling infrastructure. The area is paved with bricks and has speeds under 30 km/hour. Although there were cycle tracks and sidewalks in this area, many riders and pedestrians took to the street.

As a whole, the group did not feel stressed as bicyclists or pedestrians on this street. Our first observation was the red brick paving and piano key speed humps suggests that this area has pedestrian priority, providing measures to ensure slow vehicular traffic. Additionally, cyclists have a designated cycle track which can be seen in Figure 1 below to the right of the black fence next to the canal and to the right of the vegetated median. Our observations found that traffic by all modes of transportation occurred mostly on the eastern side of the canal, where the road continued to the museum. As previously mentioned, there were traffic calming measures implemented, likely because of the straightaway approach, seen in the photo of the speed hump. These measures resolved and reduced conflict by calming the vehicular traffic to provide more room for cyclists and pedestrians.

Figure 1. Eastern Cross Section with Bicyclists in Street not in Cycle Track

The cross sections in Figure 1 is approximately 6′ cycle track, 2′ vegetated median, 12′ unlaned road, and 10′ sidewalks with no parking on either side. Although there was a separated cycle track on the east side of the canal, there seemed to be no incentive for cyclists to use this infrastructure due to the infrequent car traffic and separation from pedestrians. As seen in all photos, cyclists rode freely down the street while most pedestrians walked on the sidewalks. The wide sidewalks had ample space for the heavy tourist pedestrian traffic seen on this Saturday afternoon. Allocating adequate pedestrian specific space seemed to remove most pedestrians from the street and allowed the bicyclists to freely use the road instead of entering the separated cycle track. However, we also found that the wide travel lanes and infrequent vehicle traffic could accommodate a number pedestrians overflowing onto the street from the sidewalk and integrating with the bicyclist traffic. The reduction of vehicular traffic, which provides a large shared space, was the greatest mitigating tactic for bicycle and pedestrian conflict.

Figure 2. Western Cross Section with Pedestrians in Street not in Sidewalk

The western side of the canal had a less direct connection to the museum and therefore saw less traffic by all modes of transportation. As seen in Figure 2 the low traffic allowed pedestrians and cyclists to navigate around each other, preventing conflict. Here the sidewalks were much narrower, but due to low vehicular traffic volumes sharing the roads was possible. Additionally, there was parking on the canal side of this road but over the course of our visit we saw no changing of parked cars.

To understand the surrounding areas feeding bicyclist and pedestrian traffic at the Spiegelgracht canal, our group also visited the intersection approaching from the museum. Unlike the spacious and less stressful area near the canal, the intersection of Spiegelgracht with Weteringschans was much more chaotic. This was primarily due to the increased number of cyclist and pedestrian interactions compared to the traffic closer to the canal. Here there were also designation of spaces on the north side of the road seen through 7′ sidewalks, 6.5′ cycle tracks, and crosswalks with 4′ medians for waiting pedestrians. This can be seen in Figure 3. As a whole these were much more crowded than the road space near the canal and forced segregation of pedestrians and bicyclists with no path alternatives. This distinct designation of road space, particularly when bordering the busier Weteringschans, increased direct conflict of cyclist and pedestrian traffic, particularly when pedestrians tried to cross the cycle track.

Pedestrians often had to wait either on the sidewalk or on the median when trying to cross the cycle track. At this intersection we saw a back up of pedestrians before they were able to cross the cycle track. There were the occasional pedestrians who sprinted across the cycle track out of the way of the bike but as a whole pedestrians struggled crossing this cycle track because of the fast and frequent bikers. Although the walkers had a safe waiting area on the sidewalk and on the center median this conflict had a direct impact on pedestrians but caused less interruption to the bicycle traffic. One option to create more of a shared space to allow better pedestrian crossings would be to implement speed reduction measures for bicyclists that made them aware of the pedestrian crossing. However, this resolution comes at the expense of the cyclists travel and a hierarchy of methods of transportation should be considered before changes are made.

Figure 3. Pedestrians and cyclists navigating Spiegelgracht and Weteringschans (southern approach from museum)

Figure 4. One of the few cars we saw

Kleine-Garmanplantsoen

As we traveled to our locations, we also stopped to observe pedestrian and bike interactions at the intersection of the eastbound side of Kleine-Gartmanplantsoen where it intersects Leidsekruisstraat. Overall, this intersection was a good example of cohesive and pleasant interactions between cyclists and pedestrians.

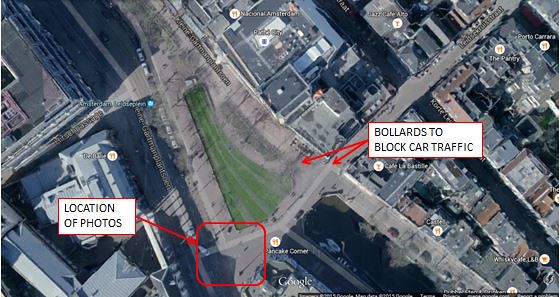

There is a small park that separates the eastbound and westbound sides of Kleine-Gartmanplantsoen and many shops and restaurants on Leidsekruisstraat, so there is a great deal of pedestrian and bike traffic. However, there are bollards preventing cars from travelling north on Leidsekruisstraat and west on Kleine-Gartmanplantsoen, so there is very little car traffic (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Plan view of intersection of Kleine-Gartmanplantsoen and Leidsekruisstraat

Kleine-Gartmanplantsoen is a very wide road, especially compared to the many narrow streets in the center of Amsterdam. There is nearly 80 feet between the buildings on the south side of Kleine-Gartmanplantsoen and the park. Next to the park there is a 8 foot cycle track. It is wide enough for two people to bike next to each other (see Figure 6).

Figure 6. The wide cycle track allows for two cyclists to comfortably ride next to each other.

In addition to the wide cycle track, there is also a sidewalk which is approximately 17 feet wide in this location, which is much wider than many of the sidewalks we observed. There is an approximately 9 foot median separating the cycle track from the travel lanes, which is wider than the 6 foot minimum needed for a pedestrian refuge.

The cycle track is differentiated from the median and the sidewalk by a gray stone curb. The cycle track is also paved with a different type of brick than the sidewalk and the median. These visual elements made it clear which parts of the street are pedestrian space and which parts are bike space. There were very few instances of bikes riding on the sidewalk or pedestrians walking in the cycle track.

Figure 7. Kleine-Garmanplantsoen looking east. The cyclist is able to travel unobstructed through the cycle track because the pedestrians are all on the sidewalk.

Because pedestrians had a great deal of space on the sidewalk, they were less likely to walk in the cycle track. When pedestrians were crossing the street, they had plenty of space to wait in the median so they did not obstruct the cycle track while they waited until it was safe to cross. Therefore, there were very few interactions between pedestrians and cyclists because each group has its own space.

With Many Cars

Leidsebosje-Stadhouderskade

This intersection contains many modes of transport leading to added complication and congestion, however pedestrian and bike focused designs lower the danger and allow for better ease of use. Some of these design features include double pedestrian refuge islands and separated bike facilities. The high number of cars require the need for advanced crossing signals and refuge islands. The multiple refuge islands are designed because of the tram tracks in the center. The design means that people cross no more than 2 lanes at a time, and both the car directions are one way reducing the injury risk. These islands give pedestrians more than enough time and space to cross the stretch of road. In a busy area, this seemed to be an example of a well designed crossing.

With the many lanes of travel and tram tracks the pedestrian and cycle tracks seem to suffer somewhat as they are cramped on the side of the road resulting in many awkward and dangerous interactions between pedestrians and cyclists. The cycle track is mostly flush with the sidewalk with a small .5-1” bump distinguishing the pedestrian from cycle space. The busy time of day resulted in a lot of intermixing of pedestrians in the cycle tracks both actively crossing the road in addition to those waiting for green signals to walk on the intersecting road. There was little space for pedestrians to wait, so they mostly stood in the one way cycle track forcing bikes to stop or change direction. The bikes are given 5’5” and pedestrians are given 6’ along the road but this drops to below 5’ next to the crossing. This cramped design resulted in bikes nearly hitting waiting pedestrians, and waiting bikes blocking the thru cycle lane. To remedy this, designers might want to consider moving the fence a few feet to allow more room for waiting pedestrians.

Video 1. Cyclist and Pedestrian Crossing

Museumbridge-Stadhouderskade

Figure 8. Cyclist Crossing in Front of Rijksmuseum

This is the area directly in front of the Rijksmuseum, the most visited museum in the Netherlands, so naturally it has a high volume of every kind of traffic. While this is a T-intersection for vehicular traffic, it is a four way intersection for bikes; they can continue straight on Museumbrug through a tunnel that goes under the museum itself. Dotted lines are extended from the cycle tracks all the way through the intersection to denote the bike lane. Pedestrians can also travel straight on Museumbrug, but they have designated crosswalks that are nearly 20 feet from the dashed bike lane. Physically separating the crossing cyclists from the crossing pedestrians makes it unlikely that the two groups will have to interact. Therefore, b0th pedestrians and cyclists can cross easily and safely without interference from the other group.

Figure 9. Stadhourderskade Cross Section

The picture above shows a cross section of the street running parallel to the canal in front of Rijksmuseum called Stadhourderskade. There is clearly heavy pedestrian traffic here, and there is a wide median in the middle to help people cross four lanes of traffic. As the picture demonstrates, this wide crossing can handle a large volume of people. Bicycles cross closer to the middle of the intersection, eliminating any conflict between the two groups.

Figure 10. Museumbrug Cyclist and Pedestrian Crossing

This is a view of Museumbrug facing away from the museum. It is a small one way street with only one travel lane. This leads to the conclusion that most of the vehicular traffic occurs on Stadhourderskade, a four lane divided through road. I personally did not witness any cars turn onto Museumbrug. However, most of the bicycles and pedestrians, for whom Museumbrug is not a dead end, will want to use this street, either to enter the museum or to explore the plaza on the other side. Because there is not much car traffic on this street, it is a low stress street for both cyclists and pedestrians.

In this case, it seems the majority of vehicular traffic is moving perpendicular to the majority of bicycle/pedestrian traffic. As a result, the area is very chaotic and potentially dangerous, but adequate signals and short crossings make it manageable. The interactions between the bicycles and pedestrians were smooth because they each had their own designated crossings and were able to move at their own speed. I did not observe any significant conflicts.