September 1, 2016 —When presented with contradictory evidence about a politically contentious issue, it’s easy to fall into the trap of reacting emotionally and negatively to that information rather than responding with an open mind. We may not only discount or dismiss such evidence, we are also likely to quickly call into question the credibility of the source. “Motivated reasoning,” defined as the “systematic biasing of judgments in favor of one’s immediately accessible beliefs and feelings,” write political psychologists Milton Lodge and Charles Taber (2013), is “. . . built into the basic architecture of information processing mechanisms of the brain” (p. 24).

But here is the surprising paradox: studies show that in politically contentious science debates, it is the best educated and most scientifically literate who are the most prone to motivated reasoning. Researchers differ slightly in their explanations for this paradox, but studies suggest that strong partisans with higher science literacy and education levels tend to be more adept at recognizing and seeking out congenial arguments, are more attuned to what others like them think about the matter, are more likely to react to these cues in ideologically consistent ways, and tend to be more personally skilled at offering arguments to support and reinforce their preexisting positions (Haidt 2012; Kahan 2015).

The intensity and proficiency with which really smart people argue against challenging evidence explains why brokering agreement on issues such as climate change, natural gas fracking, nuclear energy, evolution, and other issues is so challenging. There is no obvious solution to this paradoxical bind, and there is no easy path around the barrier of our inconvenient minds. But in talking with others, we can adopt specific practices that may at least partially defuse the biased processing of information, opening up a space for dialogue and cooperation.

Our Knowledge-Based Differences

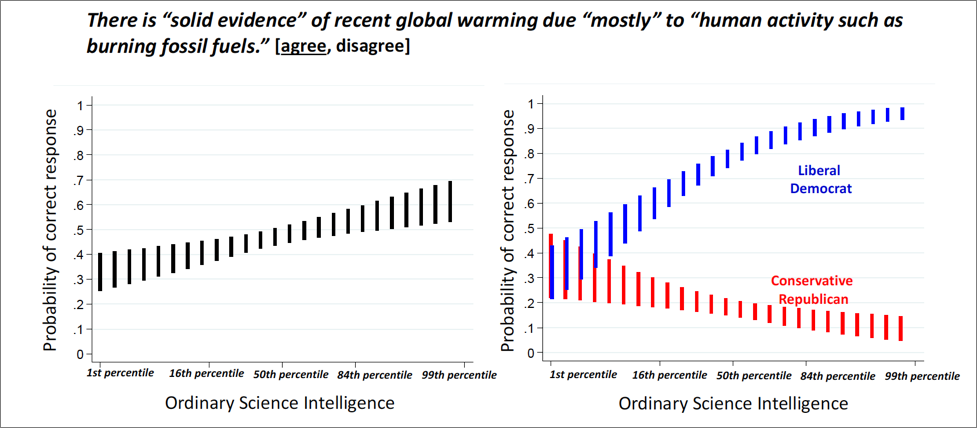

Over the past decade, researchers studying science-related controversies via public opinion surveys and experiments have documented numerous instances of smart people disagreeing in politically motivated ways. For example—contrary to overwhelming scientific consensus—studies find that better educated conservatives who score higher on measures of basic science literacy are more likely to doubt the human causes of climate change. Their beliefs about climate science conform to their sense of what others like them believe, the dismissive arguments of conservative political leaders and media sources, and their sense that actions to address climate change would mean more government regulation, which conservatives tend to oppose (Kahan 2015).

Source: Kahan (2015).

Lest you think that conservatives are uniquely biased against scientific evidence, other research shows that better educated liberals engage in similar biased processing of expert advice when forming opinions about natural gas fracking and nuclear energy. In this case, their opinions reflect what others like them believe, the alarming arguments of liberal political leaders and media sources, and their skepticism toward technologies identified with “Big Oil” and industry (Nisbet et al. 2015).

A similar relationship between science literacy and ideology has been observed regarding support for government funding of scientific research. Liberals and conservatives who score low on science literacy tend to hold equivalent levels of support for science funding. But as science literacy increases, conservatives grow more opposed to funding while liberals grow more supportive, a shift in line with their differing beliefs about the role of government in society (Gauchat 2015).

The polarizing effects of knowledge have also been observed in relation to religiosity and beliefs about evolution. In this case, greater science literacy predicts doubts about evolution among the most religious but acceptance of evolution among the more secular (Kahan 2015). But isn’t belief in evolution an indicator of science literacy? Rather than measuring scientific knowledge, studies show that questions about evolution tend to measure a commitment to a specific religious tradition or outlook. Many in the public are aware of the scientifically correct answer to questions about evolution, but if not otherwise prompted, by way of a process of motivated reasoning they are inclined to answer in terms of their religious views (Roos 2014).

For example, in 2012 when half of survey respondents were asked by the U.S. National Science Board to answer true or false, “Human beings, as we know them today, developed from earlier species of animals,” 48 percent of those questioned answered “true.” But among the other half of the survey sample, those who were asked “According to the theory of evolution, human beings, as we know them today, developed from earlier species of animals,” 74 percent answered “true.” A similar difference in response occurs when a true or false question about the big bang is prefaced with “According to astronomers, the universe began with a big explosion” (National Science Board 2014). (See also, SI, “Science Indicators 2014. . . .” May/June 2014.)

Because they are politically contested issues, asking people whether they believe in evolution, the existence of climate change, or the safety of nuclear energy is equivalent to asking people with which social group they identify. As a result, people’s responses to these questions do not reflect what people know factually about the issue or how people interpret and integrate the knowledge that they hold. Instead, such questions reflect people’s core political and religious identities. In sum, our beliefs about contentious science issues reflect who we are socially. The better educated we are, the more adept we are at recognizing the connection between a contested issue and our group identity (Kahan 2015).

A Different Kind of Conversation

To overcome motivated reasoning on topics such as climate change or evolution, some research suggests that we should look for opportunities to explicitly explain the uncertainty relative to scientific understanding and to be fully transparent in how scientific conclusions are reached and how uncertainty is reduced. From this view, it is a mistake to reply to challenges to scientific authority by arguing that the “science is settled.” A scientist’s credibility, write communication researchers Kathleen Hall Jamieson and Bruce Hardy (2014), depends on communicating that she is “faithful to a valuable way of knowing, dedicated to sharing what she knows within the methods available to her community, and committed to subjecting what she knows and how she knows it to scrutiny and hence, correction by her peers, journalists, and the public.”

Political scientist James Druckman (2015) echoes similar recommendations for overcoming motivated reasoning. A key strategy is to communicate when possible about consensus evidence endorsed by a diversity of experts, make transparent how scientific results were derived, and avoid conflating scientific information with values that may vary among the public. In this case, he emphasizes the importance of “values diversity,” in which scientists avoid offering value-laden scientific information, defining for the public a “good” or “competent” decision or policy outcome. Rather than arguing on behalf of a specific outcome, experts should work to ensure relevant science is used or at least consulted in making a policy decision.

Research by Yale University’s Dan Kahan (2010) and colleagues suggests that a possible effective strategy for overcoming biased information processing is to “present information in a manner that affirms rather than threatens people’s values.” People tend to doubt or reject expert information that could lead to restrictions on social activities that they value, but Kahan’s research shows that if they are provided with information that upholds those values, they react more open-mindedly.

For example, conservatives tend to doubt expert advice about climate change because they see it as aligned with regulations and other actions that restrict commerce and industry. Yet Kahan’s research shows that conservatives tend to look at the same evidence more favorably when they are made aware that “the possible responses to climate change include nuclear power and geo-engineering, enterprises that to them symbolize human resourcefulness.”

Cultivating Reasoning Skills

In response to research demonstrating the polarizing effects of basic science literacy, decision scientists Caitlin Drummond and Baruch Fischhoff (2015) in a recent study focused instead on testing the role of more fundamental scientific reasoning skills. If individuals possessed the skills to think and reason like a scientist, could this trump the tendency for really smart people to rely on their political and social identities in forming opinions about controversial subjects?

Drummond and Fischoff asked survey subjects eleven questions that measure the skills needed to demonstrate competence in evaluating scientific evidence or to “think like a scientist.” These questions asked about double-blind experiments, causality, confounding variables, construct validity, control groups, ecological validity, history and maturation effects in surveys or experiments, measurement reliability, and response bias.

Respondents on average answered seven of these eleven questions correctly. Individuals who scored higher on the scientific reasoning scale were better educated, more open-minded, and tended to be older. Of particular interest, scientific reasoning ability was unrelated to either political ideology or religiosity. After controlling for several confounding factors, higher scores on the scientific reasoning scale consistently predicted acceptance of the scientific consensus on vaccines, genetically modified foods, and human evolution but not climate change or the big bang. In a skills test, individuals scoring higher on the scientific reasoning scale were also more likely to correctly interpret numerical information regarding the effectiveness and side effects of certain drugs.

Based on these findings, scientific reasoning skills appear to be predictive of attitudes consistent with scientific consensus on highly contested issues (though not on climate change). The challenge is that such skills are not easily acquired once formal education ends, leaving few if any effective communication strategies for bolstering scientific reasoning among the adult population. Nevertheless, the research findings underscore the importance of teaching scientific reasoning skills as part of the high school and college-level curricula to as broad a segment of the student population as possible. At the college level, an easy first step would be to ensure that students take a greater number of rigorous science and social science courses as part of their general education requirements.

–This article appeared in the Sept./Oct. 2016 issue of Skeptical Inquirer magazine.

Citation:

Nisbet, M.C. (2016). The Science Literacy Paradox: Why Really Smart People Often Have the Most Biased Opinions. Skeptical Inquirer, 40 (5), 21-23.

References

- Druckman, J.N. 2015. Communicating policy-relevant science. PS: Political Science & Politics 48(S1): 58–69.Drummond, C., and B. Fischhoff. 2015. Development and validation of the scientific reasoning scale. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making.

- Gauchat, G. 2015. The political context of science in the United States: Public acceptance of evidence-based policy and science funding. Social Forces 2: 723–746.

- Haidt, J. 2012. The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion. New York: Vintage.

- Jamieson, K.H., and B.W. Hardy. 2014. Leveraging scientific credibility about Arctic sea ice trends in a polarized political environment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111(Supplement 4): 13598–13605.

- Kahan, D. 2010. Fixing the communications failure. Nature 463(7279): 296–297.

- ———. 2015. Climate science communication and the measurement problem. Political Psychology 36(S1): 1–43.

- Lodge, M., and C.S. Taber. 2013. The Rationalizing Voter. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- National Science Board. 2014. Science and Engineering Indicators 2014. Arlington, VA: National Science Foundation.

- Nisbet, E.C., K.E. Cooper, and R.K. Garrett. 2015. The partisan brain: How dissonant science messages lead conservatives and liberals to (dis) trust science. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 658(1): 36–66.

- Roos, J.M. 2014. Measuring science or religion? A measurement analysis of the National Science Foundation sponsored science literacy scale 2006–2010. Public Understanding of Science 23(7): 797–813.