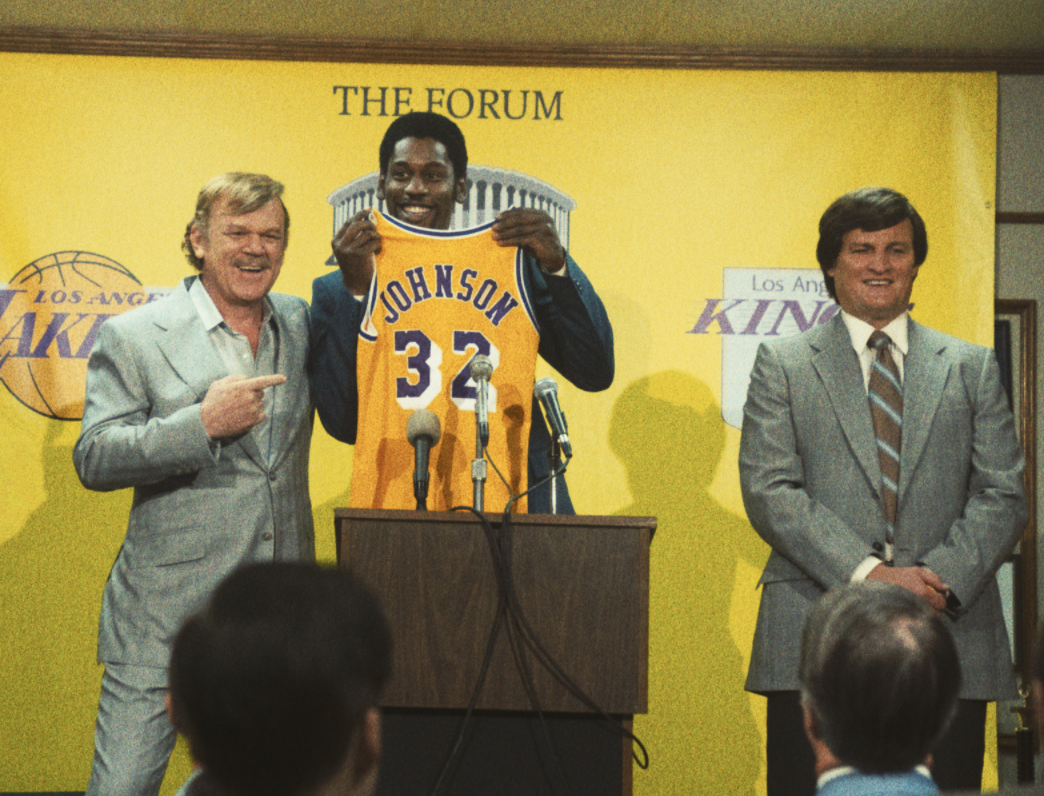

In 1979, former NBA legend and Hall of Famer, Jerry West took his 1969 Finals Most Valuable Player trophy and hurled it through an office window in a fit of rage. It landed in a hallway at the LA Lakers’ headquarters, covering the floor in shattered glass as the room fell silent.

HBO’s new series, “Winning Time: The Rise of the Lakers Dynasty,” includes this scene in its first episode, surprising viewers. But, the most surprised might have been Jerry West himself. Why? Because that never actually happened; his office didn’t even have a window.

“Hollywood is under no obligation to present your best side,” says Patti Jones, an entertainment lawyer with the firm Sennott, Williams & Rogers in Boston, Massachusetts. “Sometimes [they’re] trying to stir things up just to get attention.”

Recently there has been an avalanche of shows across various networks that provide viewers with a glimpse into the events and behind-the-scenes stories of some of the most sensational topics in recent years. “Inventing Anna,” “WeCrashed,” and, of course, “Winning Time” have all premiered in just the last two months. While the shows run on different networks and focus on distinctly unique characters and storylines, they have one very important thing in common: the shows’ creators all take liberties with the truth, using disclaimers to protect themselves against legal action. As a result, there’s not much anyone can do to stop them.

In fact, the very first image viewers see when they tune into “Winning Time” is a disclaimer: “This series is a dramatization of certain facts and events. Some of the names have been changed and some of the events and characters have been fictionalized, modified or composited for dramatic purposes.”

The producers of “Inventing Anna” make it even easier to understand, showing a statement that looks like it may have been written by an elementary school student: “This whole story is completely true. Except for all the parts that are totally made up.”

While disclaimers on television—or elsewhere for that matter—are nothing new, the extent to which producers and writers are willing to veer from the truth is starting to receive blowback. With respect to “Winning Time,” former player representative and current executive for the NBA’s Detroit Pistons, Arn Tellem, wrote in the Hollywood Reporter that the show’s depiction of West was “cruel, dishonest and staggeringly insensitive,” adding that the program was “campy, mean-spirited fiction.” Gary Vitti, a long-time Lakers trainer, walked off the set because of the way he felt West was being mischaracterized.

Best-selling author, Jeff Pearlman, whose book “Showtime” was the inspiration for the hit HBO show, spent about two years writing, doing research and interviewing over 300 sources to get to what he believes is an accurate representation of the facts; his involvement with “Winning Time” is very limited. Pearlman is quick to note that what people see on the screen will not always match his book, and also wants to remind people that “Winning Time” is entertainment based on the Lakers in the 80s, not a documentary about the team. He also says that while he personally “loves” Jerry West and has “a ton of respect for the man” there is what he describes as a “Jerry West sainthood movement” taking place.

“The facts are he was really [a] difficult [person],” Pearlman says. “[West] hired a private investigator to trail Norm Nixon because he thought Norm Nixon was a drug addict. He would berate [members of the] Lakers’ staff. So on the one hand I totally get it. I just think this reaction that Jerry West is the Mother Theresa of basketball and never did anything wrong is just a little over the top too.”

And herein lies the crux of the issue: Under a disclaimer, the truth—of West’s or anyone else’s life, for that matter—is legally open to interpretation. HBO has the rights to the book “Showtime” and a disclaimer that allows them to tell the story the way they want. In their minds, a trophy through a window is great television.

While character depiction in “Winning Time” has generated a fair amount of disagreement and controversy, HBO has also gone so far as to produce the show without obtaining permission to use the Lakers logo or other trademarks owned by or associated with the league, something both the NBA and the team have refused to comment on.

So HBO is airing a show portraying well-known, real-life people—many of whom are wearing Lakers uniforms—doing things they didn’t do. They could, if they wanted to, even change the scores of the actual games that took place.

“I don’t think the average person will know if it’s true,” says Paul Litwin, an entertainment lawyer who has provided representation for professional NFL, NBA and MLB players in a variety of matters. “[People] won’t look at the disclaimers. They don’t care. They just want to be entertained.”

Litwin said the true issue at hand is around damaging someone’s character, or, as it is legally defined, defamation. The disclaimers, Litwin notes, are not to educate viewers that what they are watching may not be true. They serve, first and foremost, to protect the show’s creators from liability; whether someone reads them is irrelevant. In terms of defamation, Litwin notes that it can be tricky to litigate, especially for celebrities. The burden of proving that a show’s creator acted with actual malice or intentionally tried to harm them can be particularly difficult.

Therefore, while anyone depicted in any movie or TV show could theoretically sue for damages, it could be a challenging road to travel. Despite the obstacles, a high-profile case was filed in 2021 by Georgian chess legend Nona Gaprindashvili, who is claiming defamation by Netflix for its show “The Queen’s Gambit.” The show stated that Gaprindashvili had never faced men, something that is factually false. Netflix claimed that since the show is a work of fiction, the suit should be dismissed, but U.S. District Judge Virginia A. Phillips disagreed. In January 2022, Judge Phillips stated in her ruling that “The fact that the Series was a fictional work does not insulate Netflix from liability for defamation if all the elements of defamation are otherwise present.” As of publication, the $5 million case is still ongoing.

Even if someone did decide to sue, it comes with an element of risk. Details of their lives, especially if they are a celebrity, could become public through the legal discovery process, something that could prove to be more damaging than the show itself. For example, in “Showtime” Pearlman describes in great detail the prevalence of drug use, prostitution and other questionable behavior that involved members of or people associated with the Lakers, things that many people probably don’t want to discuss 40 years later.

Disclaimers provide studios with a tremendous amount of flexibility and protection, acting as both an elastic band for the truth and a shield from which to hide behind when the legal arrows begin to fly. It seems to be a process that favors the producers and creators, something that, while legally sound, seems unfair for the person mischaracterized, whether that person is well known or not.

“[To the studios] it’s not about what feels right. It’s not about what’s fair,” says Litwin. “It’s all about what’s actionable under the law.”