Despite a globalizing game, Americans still make up 80% of NBA rosters. For that 80%, the path to the league after high school has traditionally been much more singular than those of their foreign counterparts. Top recruits generally attend college for a year then get drafted, or, play multiple years in the NCAA and hoping their draft stock rises (and that they stay healthy long enough to cash in).

Since 2005, just 12 Americans have played in an NBA game without attending college. Over the past few years however, the spectrum of opportunities for American high school prospects has been broadening and the views of the NCAA and the advantages of college ball have been changing.

As of 2021, athletes from the United States had to be at least one year removed from high school to be eligible for the NBA Draft. Some players, like 2020’s third overall pick and 2021 NBA Rookie of the Year LaMelo Ball, chose to play professionally in a different country for a year before the NBA. Others, like 2021 top-10 picks Jalen Green and Jonathan Kuminga, selected to play in the NBA’s developmental league, the G League. Most high school prospects however elect to play college basketball, many for just a single season in order to meet draft requirements.

There has been recent criticism by NBA athletes who see the “one and done” trend as more of a detriment than a benefit for the players. A large critique of the NCAA has been their lack of compensation for athletes and particularly their exploitation of basketball players. Philadelphia 76ers star Ben Simmons was particularly frustrated with his experience during his one year at LSU and the “education,” or lack thereof, he received at the accredited university.

“Everybody’s making money except the players,” Simmons said in the 2016 Showtime documentary, One & Done. “We’re the ones waking up early as hell to be the best teams and do everything they want us to do and then the players get nothing. They say education, but if I’m there for a year, I can’t get much education.”

The alternative to the one year playing in the NCAA can be quite fruitful for some athletes. The G League’s new team, G League Ignite offers six figure professional contracts to top high school recruits and gives them the opportunity to play against more experienced competition. Perhaps the most decorated recruit to join Ignite for the 2020-21 season was ESPN’s top 2020 prospect, Jalen Green. Green signed a contract worth $500,000 with the team and went on to lead Ignite in points before being selected second overall by the Houston Rockets in the 2021 Draft.

Green spoke about his decision to play in the G League rather than college on his Instagram Live in April of 2020, and cited the potential for development in the G League. “I think the main reason for [signing with the G League] is I wanted to get better, I wanted to develop a better game so that way I can be ready for the NBA,” Green said. “I think this is the best route to prepare myself [for professional basketball].”

Two members of the 2020 Draft chose a less traveled route after high school. R.J. Hampton and LaMelo Ball each took professional contracts in Australia’s National Basketball League. Both players were five-star recruits out of high school, but experienced differing levels of success in their year prior to the NBA. Ball won the league’s Rookie of the Year Award while playing 12 games for the Illawarra Hawks and was drafted third overall by the Charlotte Hornets. Hampton on the other hand scored fewer than nine points a game over his 15-game stint for the New Zealand Breakers and saw his draft stock fall from being a top five pick to being selected 24th overall by the Milwaukee Bucks.

The History

Ball, Hampton and Green are part of a new wave of talent that are approaching the path to professional sports from a different angle, but they are far from the first.

The league’s history with high schoolers can be separated into three rather distinct eras: prior to 1971, 1971-2005, and from 2005 to the present day.

Up until 1971, the NBA required players to be four years removed from high school to be eligible for the Draft. After the 1971 Supreme Court ruling on Haywood v. National Basketball Association allowed players to bypass the four-year rule, two players were selected out of high school in 1975, Daryl Dawkins and Bill Willoughby. For 20 years after that, nobody was selected directly from high school (though several players, like Michael Jordan, left college early), until a 10-year stretch from 1995 to 2005 where 35 Americans were selected. Among those 35 were 10 future All-Stars, three future Hall of Famers and active stars LeBron James and Dwight Howard. In 2005, the current rules came into effect, and it was declared that a player must be at least 19 years of age and one year removed from high school to play in the NBA.

Since 2005, seven of American NBA players who did not attend college played professionally for at least one year first, and seven have been drafted and signed in the last five years.

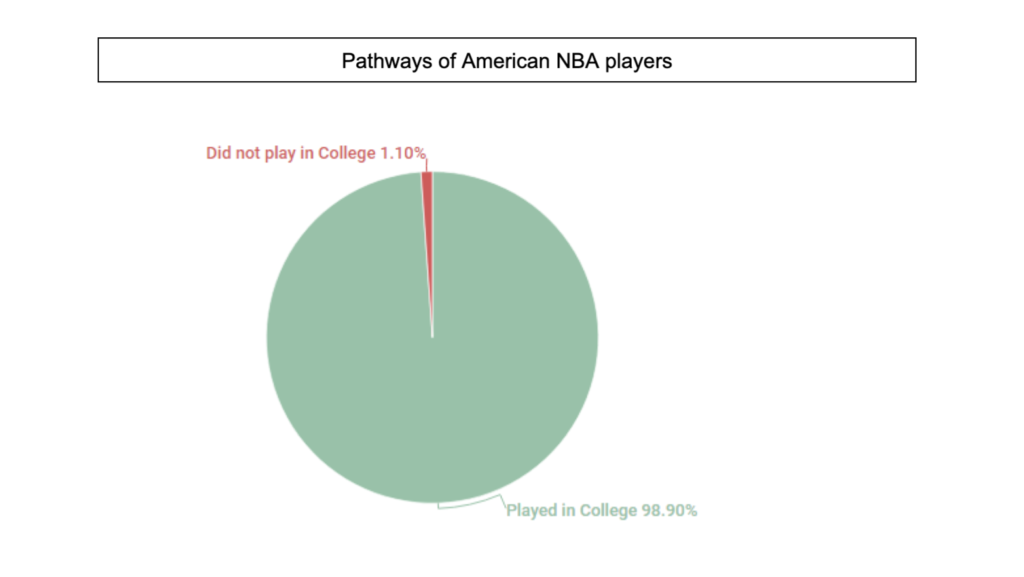

Throughout the history of the league however, over 4,300 American NBA players have previously attended college, while just 48 never did. The following charts take a more targeted look at this player pool.

Of the 48 Americans to play in the NBA and not attend college, nearly half were lottery picks, players selected within the top 14 picks of a given NBA Draft. This meant that the players who did elect to skip college were considered some of the very best that America’s high schools had to offer. The batch from 1995-2005 had three players selected first overall (Dwight Howard, Kwame Brown and LeBron James) and three MVP winners (Kevin Garnett, Kobe Bryant and LeBron James).

It is a small sample size, but 10 out of the 48 players that didn’t attend college made All-NBA teams, an 18-percent mark during any given NBA season. In contrast, just one out of every 30 NBA players, or 3.3% of the total NBA player pool, is selected to an All-NBA team.

The Future

The number of American players opting for professional contracts prior to entering the NBA Draft has been trending upwards in recent years. Some athletes claimed level of competition as their reason for going pro while others focused more on the monetary potential of professional leagues. This year however, the NCAA has made drastic changes that may impact how players choose their paths to the NBA moving forward.

At the beginning of July 2021, the NCAA changed their tight rulings on the ways that their athletes can profit off of their name, image and likeness. These rule changes were made in response to a June 21 Supreme Court ruling in which the Court voted unanimously in favor of former NCAA athletes who were suing the NCAA due to their rules preventing student compensation, citing anti-trust laws and The Sherman Act. These changes now allow students to promote themselves and make a profit while in college, something that was forbidden for years.

Still, Northeastern University athletic director Jim Madigan, does not necessarily see this ruling changing the landscape of athletes opting to play professionally rather than going to college.

“I think a lot of the top prospects who may have considered going to the G League or other professional leagues solely for monetary gain may rethink that now,” Madigan says. “There are other players however, who simply thought the competition may be better than in the NCAA, so they won’t be swayed by the new changes.”

The NBA Commissioner’s Office has not made any move to stop high school prospects from playing in the G League following the NCAA’s recent ruling.

NBA Commissioner Adam Silver does not seem to have any regrets when it comes to the creation of his Team Ignite. “We created Team Ignite in the G League as an opportunity for players who choose not to go to college and want to become professionals,” Silver says. “They can go directly into the G League and be well compensated.”

As of this point, the success of players like Jalen Green and Jonathan Kuminga seems to have convinced other top prospects of the potential of the G League. Jaden Hardy, a top-five prospect in the class of 2021, signed with the G League this season. For now though, the majority of prospects are still going to try their hand at college ball with 35 of 247 Sports’ top 50 prospects in the 2021 class having committed to a school, perhaps due to the new potential for compensation under new NIL guidelines.

The next few recruiting classes will be important when it comes to seeing if the top prospects will continue considering other options beyond the NCAA. The G League’s Ignite completed its first season and produced three draft picks, including two within the top 10, and the NCAA will now allow players to be compensated while playing in college. The coming years will tell if prospects still want to play in other leagues for the different types of competition or go to the NCAA and have similar money-making potential if not greater. How high schoolers in America are getting to the NBA is changing, now the question will be how much will things change and what will those changes look like on the professional hardcourt.