Photo: University Libraries, Archives and Special Collections, Northeastern University Department

“Urban renewal” is not an alien concept to city neighborhoods but the process usually occurs only once. Boston’s South End is one of the few that can claim to have gone through the metamorphosis twice. Nearly fifty years ago, residents partnered with the city to rebuild and update broken down rowhouses, strengthening the community. Now the residents face Round Two. Since 2000, gentrification driven solely by private real estate developers, has led to rising housing prices that force out the original tenants and threaten the neighborhood’s identity.

In the early 1960s, the city moved to demolish the South End's Parcel 19, a largely Puerto Rican community between Tremont and Washington Streets. Through the Boston Redevelopment Authority (BRA), now known as the Boston Planning and Development Agency or BPDA, the city had brought its campaign of urban renewal to the South End. The BRA plan targeted tenements that were notorious for their substandard conditions, but planned to replace them with housing too expensive for residents, potentially pricing them out of the neighborhood.

Rather than simply protest the development of their neighborhood, the people of Parcel 19 crafted their own plans with the help of architect John Sharon, who even traveled to Puerto Rico to bring a similar style to the renovated neighborhood. If they could not stop the change, they could at least ensure they had a say in it. The result was Villa Victoria, or “Victory Village”, in conjunction with the BRA, a vibrant Puerto Rican community that endures to this day.

“I can’t think of another successful urban renewal project where the community worked with the BRA”, said Lauren Prescott, Executive Director of the South End Historical Society (SEHS) which was established in 1966 to preserve history in the face of urban renewal.

Despite the best efforts of the previous generation, the effects of gentrification are making themselves felt yet again, even at the heart of the neighborhood, Villa Victoria. On the corner of Shawmut Avenue and West Brookline Street sits the office of Inquilinos Boricuas en Accion (IBA), the non-profit organization that grew from the original Parcel 19 protests. IBA works to engage residents through education and arts programs, honoring the legacy of the Puerto Rican activists who made the community a reality. William David Nunez grew up in Villa Victoria and now works for IBA’s Resident Services Program as its Community Building Coordinator. But Nunez, himself, commutes from Rhode Island as the rise in housing costs have made it unfeasible for him and his family to live in the neighborhood where he was born and raised, and which he now serves. Ironically just the thing the forerunners of IBA worked to avoid.

What is happening now is “super gentrification,” said Rylee Kirkpatrick, a server at Parish Cafe, a local bar that has been in business for nearly eight years, on the corner of Tremont and Mass Ave. She has seen the turnover in the neighbourhood reflected in the change in customers as entire lots have been demolished to make way for residences marketed to the ultra-wealthy. These newer residents, many of whom only live in the area part of the year, do not share the same connection to the community, said Kirkpatrick, as opposed to the “tight knit community….the regulars are who keep us in business.”

Kirkpatrick recounts a recent incident which made an impact on her. A man staggered into the cafe looking confused and unable to speak. People turned away or pretended they didn’t see him, assuming he was high on drugs. When he fell to the floor, Kirkpatrick recognized he was having a seizure and called 911. EMTs arrived and took him to the hospital. The next day, the man returned to thank Rylee. He had a job and a home, as opposed to being the homeless drug addict that bystanders had assumed. Unfortunately, she observed, the attitude displayed is all too common in the historic Boston neighborhood. Gentrification is breaking down the once close community and building walls between demographics, just as much as luxury condos.

Long time resident Judy Hall remembers a very different neighborhood. In the 1960s, “people would connect across racial and economic lines.” The area drew those who had nowhere else to go, populated by senior citizens, African American families in Cathedral Project and Hispanic families on West Brookline street. A far cry from the luxury condos, rooms could be rented for as little as five dollars a week, 20 if you wanted to live large. Now, an apartment rental around the same area can go for an average of 2,700 dollars on Zillow. Even allowing for inflation, the price jump is staggering. The city-wide average rent in Boston is 3,016 dollars.

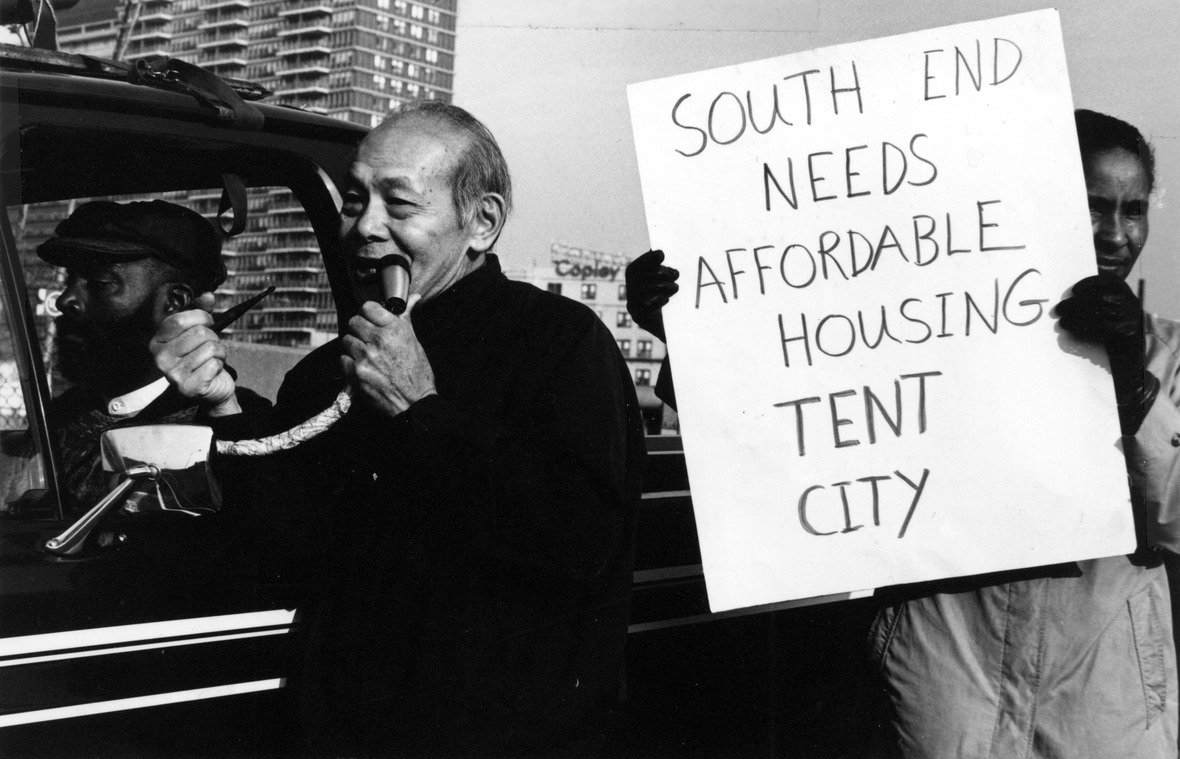

Hall and her husband, Doug, moved to the four square block of housing known as Parcel 19 as graduate students. “We were looking for vitality wherever we could find it,” said Doug and a “mishmash of wooden houses and tenements” fit the bill. When the BRA marked the area for demolition to make way for luxury housing, the Halls were at the forefront of the community resistance. “It was the 60s so there were a million causes” explained Doug, one of which was the lack of affordable housing. Doug participated in events outside of Parcel 19, including the 1968 “Tent City” protests but ruefully said he arrived too late to get arrested, a badge of honor for any serious demonstrator. Tent City was a South End-wide event, the largest demonstration taking place on April 23 of that year, in which residents protested construction of luxury apartments.

The Halls were among the founding members of the Emergency Tenants Council (ETC), that provided the community with a much needed voice in communicating with the BRA. The ETC was able to show “we had a better plan, more informed than what the city had,” said Doug.

So what prevents the communities of the South End from coming together again to protest the effects of the current “super gentrification” on their neighborhood? Alison Barnet, author of South End Character: Speaking out on Neighborhood Change, and who has lived in the South End for 54 years, says it is simply “a different time.” A cultural shift away from traditional activism such as marches and sit-ins, and towards social media and internet presence has changed the way communities respond to unpopular developments. “Activism had more effect in the 60’s” said Barnet. Now, calling for the preservation of a historic building means creating a Facebook page rather than a petition (which have also moved online), with ‘likes’ instead of signatures. People are less inclined to gather in person, which Barnet attributes to a lack of “courage.” Whether or not that is the case, it is true that events such as the Tent City protest are far more rare.

The shift at the start of the 21st century was more gradual, making it difficult to rally the community to take a stand. The end result is still the same - the cost of living continues to rise in order to draw in a different class of resident, pushing the old community out. Many have moved out of the city to surrounding communities with more affordable housing. Slowly but surely, the tight-knit communities are broken down, to be replaced by wealthier tenants looking for second homes. “[Gentrification] is really a money thing - all the real estate companies are making big bucks,” said Hall, who is concerned that with housing growing less affordable, vulnerable demographics are falling through the cracks. “With all this new and expensive housing,” Hall asked, “where are all the ordinary people going to go?”

Arnesse Brown and the Tenants’ Development Corporation (TDC) work to answer that question. The TDC was established in 1968 and aims to help low-income families find safe and affordable housing while remaining in the South End. “We have generations of families who have lived in the South End” because of the TDC’s work, said Brown, the organization’s Director of Corporate Relations as well as historian. Remaining in the area is more than a matter of sentimentalism. This is a “resource rich area”, providing services that low income families need which they cannot find in other in suburban neighborhoods.

The challenge for Boston’s South End is preserving its cultural presence while building a sustainable future. SEHS applied to have the South End listed on the national directory of historic places as the largest victorian district in US. However, the forces of progress are putting pressure on this neighborhood, and longtime residents wonder: is there a place for them?

Photos: Yuan Tianaa