Neighborhood in Transition

Zach Ben-Amots, Jianuo Han and DJ Wassick

Forest Hills only has two consistent, defining features: change and a train station.

For at least five years, the Forest Hills station has been surrounded by a maze of development. East and south of the station, land has been razed to make room for apartment buildings. Both Washington Street and Hyde Park Avenue, the major streets that intersect at the station, are lined with new business complexes and luxury condos under construction.

After six years and over $80 million, the most visible and contentious construction project in the neighborhood is finally nearing completion. The Casey Overpass Bridge -- which for 70 years spanned the heart of Forest Hills -- has been replaced by the Casey Arborway Project, an initiative managed by the Massachusetts Department of Transportation (MassDOT).

And with the completion of the Casey Arborway Project, Forest Hills may finally develop a neighborhood identity and a connection to surrounding areas.

“There’s no pride in Forest Hills,” said Richard Heath, a local historian and activist. “If there’s no pride in a place, it can easily disappear, easily change, easily be rearranged.”

When Heath first arrived in 1976, neighborhood residents were energized and optimistic. They had successfully prevented a well-funded initiative to pave over Forest Hills with a highway. The Massachusetts Department of Public Works had proposed a plan to connect Interstate 95 through all of Eastern Massachusetts, from the North Shore through Boston. Residents in every region fought the proposal on environmental and housing grounds, but the biggest displacement was expected in southern Boston.

A 1967 article in The Boston Globe reported that the project would, “force out about 725 persons, including 200 families and 70 elderly men and women, and almost 70 businesses and other institutions.”

“The I-95 story has entered into Boston mythology,” Heath wrote in A History of Forest Hills, which was published by the Jamaica Plain Historical Society. Throughout the late 1960s, state and city officials had seized land and demolished buildings to make room for the highway. “But demolition came to a halt at Forest Hills because, in 1969, people stood up and stopped I-95 at the moment when the wreckers were bearing down on Hyde Park Avenue.”

When the community stopped the expansion of I-95, they preserved their neighborhood. But the bitter fight left the community with a sour, distrustful aftertaste.

And in 2012, when MassDOT announced a plan to modernize the Forest Hills train station, along with the major intersections and freeways on either side, another fight began.

This time, the dispute focused on a decrepit bridge. The Casey Overpass Bridge was falling apart. MassDOT had two options: rebuild it or replace it at ground-level, also called “at-grade.” HNTB, the consulting firm that MassDOT selected for the project, recommended the latter option after a three-year preparation and evaluation process.

Jonathan Kapus, a design consultant for HNTB, managed the planning and design. “The goal of the project is to remove an existing structurally deficient bridge and reconnect the previously discontinued Arborway, while balancing the different modes of transportation: bicycle, pedestrian, transit and vehicular traffic,” Kapus said.

Early on, the project managers recognized that, more than usual, they would need to keep the public informed and involved. The outreach campaign for the Casey Arborway project was extensive. It involved two major public meetings during the planning phase, four more during construction, weekly “office hours,” a dedicated project website, near-weekly email updates, a phone line, and more.

“By far, this is the most robust public outreach that I’ve ever seen on any construction project. It’s multi-layered, and the information is given out as quickly as possible,” said Chris Evasius, an assistant district construction engineer for MassDOT. Evasius oversaw construction for the project.

Some residents were ardently opposed to the plans for demolition without a replacement bridge. Leaders in nearby neighborhood organizations created their own pro-bridge website, and community meetings were frequently the site of protests. Pro-bridge advocates did not believe ground-level replacements could accommodate the volume of traffic in Forest Hills.

Reactions may have seemed familiar, if you consider the neighborhood’s fight against I-95 in the 1960s. But in reality, the two projects were nothing alike.

The Casey Arborway Project has not caused any displacement. And unlike the highway, which would have replaced nature with concrete, the current renovation is actually adding green spaces, making Forest Hills part of the Emerald Necklace by connecting Arnold Arboretum and Franklin Park.

Clay Harper, a 20-year resident who writes a blog titled #ArborwayMatters, viewed the resistance to the project as ill-informed and misplaced frustration.

“There is a small ‘c’ conservative resistance to change. As progressive as [Jamaica Plain] is, there’s a resistance to change when it seems radical,” said Harper. If the bridge was still intact, according to Harper, the Emerald Necklace would have remained disconnected indefinitely.

Debate has dissipated. But MassDOT has still encountered a fair number of challenges.

Today, as it nears completion, the Casey Arborway Project is over a year behind schedule and more than $10 million over their initially proposed budget.

Harper does not blame MassDOT for the scheduling issues. Insead, he said that the sheer number of stakeholders - the city of Boston, Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation, MBTA, and community members - created a need for approval at every step. That issue combined with the massive snowstorm during January 2015 - when construction was slated to begin - which made it impossible for MassDOT to stick with their planned schedule.

Regarding budget overruns, Evacius and Kapus both spoke about late additions to the project. Specifically, MassDOT is constructing a centralized busway with a new canopy, which was not included in the initial budget.

“The bid was around $60 million, and then there was about $14 million in expected contingencies, which can be traffic police, which can be what we call overruns - which is more work than we thought there was going to be,” Evacius said. “The largest singular add was, we added the canopy, which was not part of the contract. It was certainly part of the public effort, so it was added to his contract. And that’s around $10-11 million.”

According to Evacius, MassDOT did not go over budget. They always anticipated spending $74 million, and stakeholders requested new construction elements that brought up the cost to nearly $86 million.

However, early documentation listed the cost of the “at-grade” solution at only $53 million, which was projected to be $30 million cheaper than a bridge replacement.

Despite MassDOT’s and HNTB’s “robust outreach campaign,” some residents have found both organizations to be opaque. Richard Heath has always espoused MassDOT’s ground-level project, but called their communication terrible. “They don’t tell us anything,” Heath said.

Regardless of budget, timeline and communication, construction is almost over.

The new roads and intersections are now fully constructed, and MassDOT plans to synchronize the traffic lights in the coming months. New bike lanes and wider sidewalks have opened up all major roads for safe travel by multiple modes of transportation. Bus terminals have been consolidated, and new bus exit routes have diminished the delays for many T riders. The new station has natural light pouring in from every side. Still to come are additional station entrances across the wide Arborway road, a canopy for the new bus depot and fully-synchronized streetlights to eliminate traffic delays for vehicular traffic.

The Casey Arborway Project has dominated headlines. However, the current transformation of Forest Hills goes beyond transit. The neighborhood has also seen a sharp rise in luxury condo development.

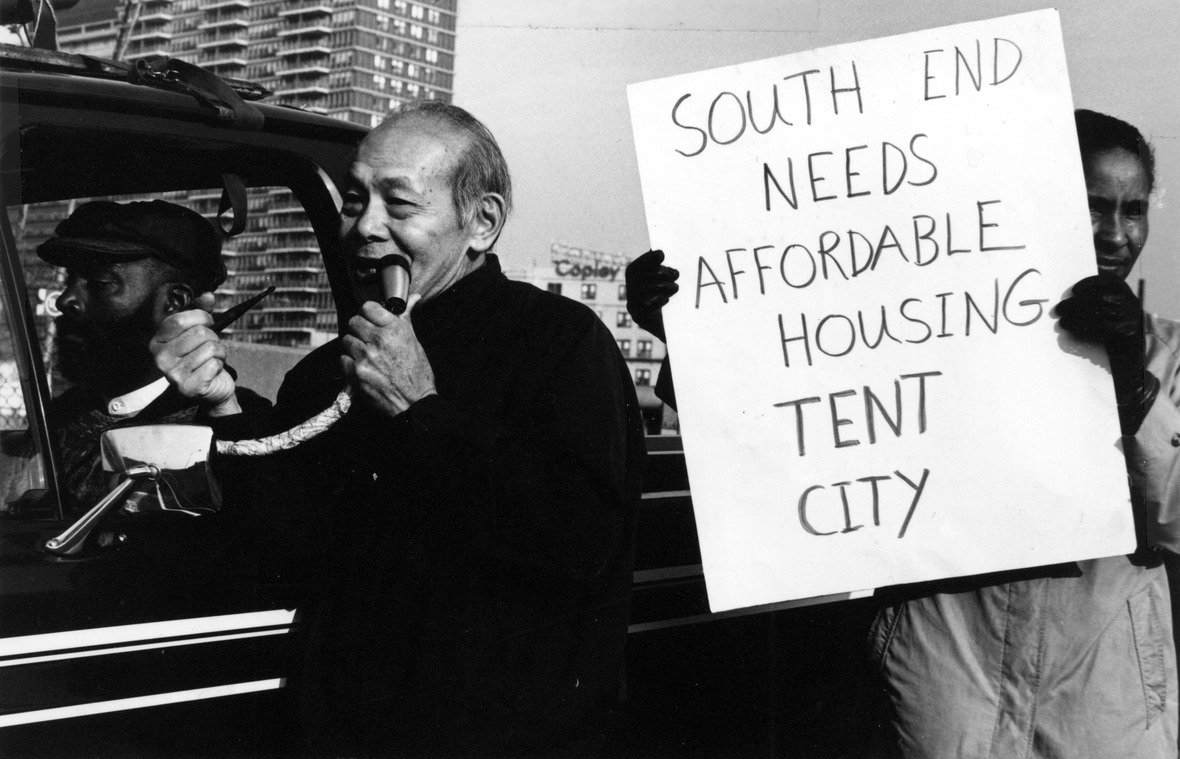

Heath is far more concerned with those housing changes; he has noted a lack of affordable housing and a diminishing working class population.

“The real tragedy is the demographic changes - the economic diversity is gone. There’s no middle class, hardly any working class here.” Heath blames the end of rent control in the 1990s for the loss of economic diversity.

According to estimates from the U.S. Census American Community Survey (ACS), Heath’s claims are largely true - if hyperbolic. In a five-year average from 2007-2011, the median household income in Forest Hills was $58,935. In the next average, between 2012-2016, the median income rose to $67,027. Over the same time periods, median gross rent increased from $1,019 to $1,385 and median home value grew from $311,500 to $382,000.

Those amount to a 36 percent in median gross rent and 27 percent in median home value. By comparison, during the same period of time, the increases for the entire city of Boston were 11 percent in median gross rent and 11 percent in median home value. Both the entire city and the Forest Hills census tract saw an increase around 14 percent in median household income.

Income, rent and home value all rose. But the truly staggering changes were demographic.

Between the two five-year averages, the white population grew from 37 percent to 46 percent. Meanwhile, the black, Hispanic, Asian and foreign-born populations all dropped. The Hispanic population experienced the steepest decline, from 34 to 27 percent. And as it becomes less diverse, Forest Hills is also becoming denser, growing growing in population from 5867 to 6547.

Forest Hills is missing many of the indicators of a historic Boston neighborhood. Unlike many of the city’s other historic areas, there is no blue ‘Welcome to Forest Hills’ sign. Unlike other business districts, there is no Forest Hills Main Streets coalition.

And along with that, residents have not seen many political allies at the local or state level. Forest Hills is part of City Council Matt O’Malley’s district. O’Malley declined to respond to multiple requests for comment.

“If Matt O’Malley stood up and said, ‘Forest Hills is the center of my district. It’s one of the most important parts of my district,’ That would change peoples’ minds, 180 degrees. He’ll never say that,” Heath said. “Elected officials have walked away from Forest Hills, every blessed one of them.”

Although O’Malley did not respond, City Councilor-At-Large Ayanna Pressley sent the following prepared statement: “Every city is a tapestry of its neighborhoods. Boston is made up of 22 unique and distinct neighborhoods that are strengthened by their diversity and their people. Jamaica Plain, and Forest Hills specifically, is dealing with the citywide trend of rising rents and the threat of displacement. Everyone deserves a home, and the people that have made the city a great place to live, work and play are at risk.”