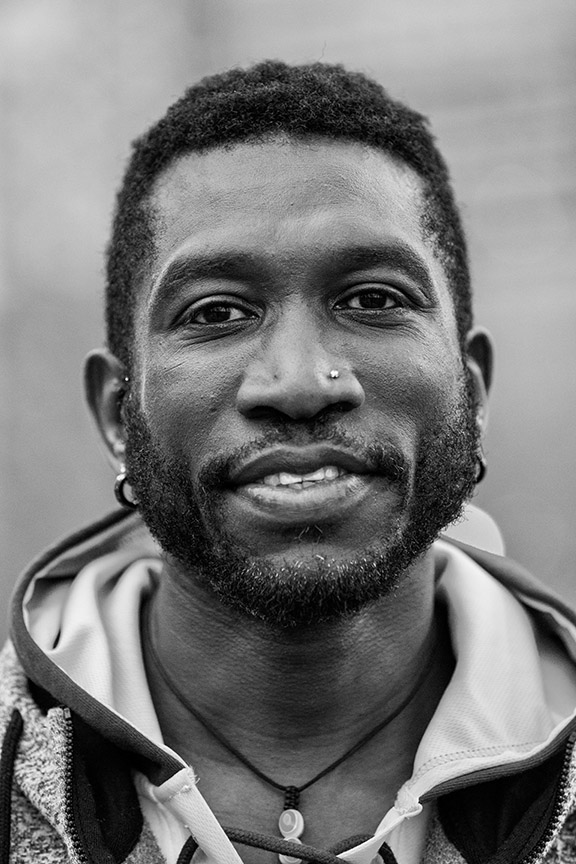

From the backseat of his car, John Wambere seems like an average Lyft driver. He offers an amiable greeting and tries to strike up a conversation if his customers seem in the mood, and he provides a clean, pleasant ride as they travel to destinations across Boston.

His customers may see an African immigrant trying to make a living, but they don’t see the full picture. They don’t see a high-profile LGBTQ-rights activist from Uganda, and they don’t see a political asylee who escaped persecution, perhaps even death, to come here

Wambere, 45, fled Uganda several years ago to protect himself and his family after the national media there outed him and other individuals as gay and the president at the time signed a bill that would imprison LGBTQ individuals for seven years and could even lead to their execution

The U.S. gave Wambere political asylum in 2014. He has been trying to rebuild his life since then in Cambridge, driving part-time for Lyft as a way to provide for himself and his daughter as he pursues a sociology degree at Boston College. He sends most of the money he earns to oppressed LGBTQ individuals throughout the world, including the activist group he co-founded in Uganda, and driving helps him do that while paying for a means of transportation.

“I was like, ‘OK, I think I could be able to take a car and then start driving and be able to pay back the car and still save some money,” Wambere said. “Part of the money paid my tuition, which is amazing.”

Finding work in a new country has always been difficult for immigrants. Many of them come to the U.S. with little money and no connections. Combine those challenges with a language barrier and a skills gap, and their options can be limited. The gig economy, where consumers use apps to find workers offering services, lowers the substantial barriers that immigrants have historically faced, but it sometimes comes at the cost of giving up protections found in the traditional workforce.

“Our economy can't function without people who are willing to take these jobs that regular Americans are not willing to take,” said Sheila Puffer, a professor of international business at Northeastern University. “Either the pay is too low or the conditions are just unappealing and unsatisfactory to the vast majority of native-born Americans.”

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics data from 2017 support Puffer’s assertion about the types of jobs that immigrants and native-born Americans are willing to do. Native-born Americans were much more likely to hold jobs in the management and professional sectors, while immigrants are 50 percent more likely to work in the service sector.

Percent in service sector

Wambere’s first job in the U.S. was part-time at a call center, where he struggled to communicate with his customers for six months. The calls were scripted, but many of the customers complained about his accent.

He also had no problems openly telling customers he couldn’t do something for him, a cultural difference to which they weren’t accustomed. That caused some friction, so the management asked him to find a better way to diffuse difficult situations.

“A few clients understood and a few said I spoke well, but … you can't please everybody,” Wambere said. “And because after every call, a survey is taken, based on the survey they had told me that I was not able to hold the job.”

David Liang, a 35-year-old Chinese immigrant living in Medford, stopped working in his family’s restaurant to drive for Lyft and Uber full-time because the companies offered him freedom and flexibility missing from hourly jobs. Because of the communication barrier, he said immigrants find work easier for companies like Lyft and Uber because almost anyone can do it.

Liang needed to tune up his car and do a background check before driving for Lyft and Uber, but the process of signing up to drive was relatively simple compared to finding work in the traditional workforce.

“Lyft and Uber don't ask you for a degree,” Liang said. “They don’t ask you for experience, as long as you have a vehicle and know where you go.”

The only things needed to sign up to drive for Lyft and Uber is a valid U.S. driver's license, proof of insurance, an approved four-door vehicle and proof of where the driver lives. Refugees and political asylees may or may not be able to work for gig companies depending on their ability to provide documentation, but most immigrants are able to start working almost immediately as long as they have proof of residence and the necessary tools for the job, like a car.

Since gig workers are considered independent contractors, they handle taxes themselves and don’t receive employment benefits from the companies that hire them. Some gigs don’t even require interviews.

Gig companies follow the laws in each state, but this type of work has grown so much and so quickly that some states are still trying to figure out how to respond with worker protections in legislation.

“And then she said, ‘Oh, I’m so sorry, I don’t mean to yell at you.’And almost at the end of the trip it started again. People are crazy.”

David Liang

Massachusetts Registry of Motor Vehicles policy requires people to prove their presence in the U.S. is lawful before they can receive licenses and register their vehicles. If an immigrant is only approved to live in the country temporarily, their license and registration will expire when their legal stay officially ends.

“The money’s OK as long as you’re willing to work,” Liang said.

Karen Chen, executive director of the Chinese Progressive Association, suggested immigrants are more likely to take gigs because they are a convenient way to make money. From her experience, immigrants don’t always use traditional apps like Uber, Lyft, DoorDash, and TaskRabbit.

Gig apps generally require workers to sign up, go through a vetting process and fulfill other various requirements, so finding gigs on apps that allow them to remain anonymous or off the books can be easier, especially if immigrants don’t speak English or have documentation.

“In general, with the gig economy and labor laws, a lot of regulations are not catching up to technology,” Chen said. “So, when something goes wrong, workers are not protected.”

For example, WeChat -- a popular messaging app among Chinese immigrants -- is being used for finding work, even though that isn’t its intended purpose. Gig work found there is much more informal because the app doesn’t have a way to monitor how the workers are paid, or if they’re paid properly.

Chen helped one man who used WeChat to work for several Chinese restaurants as a delivery driver. The man told her that he sometimes didn’t receive his full pay and other times would even be paid in Chinese money instead of U.S. dollars.

“We were having a lot of trouble trying to figure out his actual hours, what kind of labor protection he had,” she said. “At one point, it was very difficult to actually calculate what was owed and what was paid.”

Gig companies don’t appear to discriminate against people in their hiring practices, which can be significantly different from traditional jobs in the workforce, but that doesn’t mean the customers are. Workers also face problems in the gig economy beyond underpayment, and immigrants are particularly vulnerable to some of them.

Wambere faced racism from a man outside his car when dropping off a customer. The man spat at Wambere; his customer actually stood up for Wambere, but he felt humiliated.

“I felt so angry about that,” Wambere said, noting that part of being an immigrant means not feeling the freedom to respond to such insults. “I had to de-escalate myself.”

Haitian immigrant Jean Valcourt, 47, is a full-time surgical assistant at a health center in Waltham but works almost as many hours for Uber on the side. He has also encountered racism as a rideshare driver, but not as overtly as Wambere.

Valcourt can tell there’s a problem when customers don’t respond to his greetings or interact with him. He has received low ratings for seemingly no good reason, so he feels like he has to do more to make his customers happy -- like carrying luggage to his car if he sees they are going to the airport -- to keep a good rating as an immigrant.

“I guarantee you, you are going to have people who are very racist,” he said. “I just feel the way people act.”

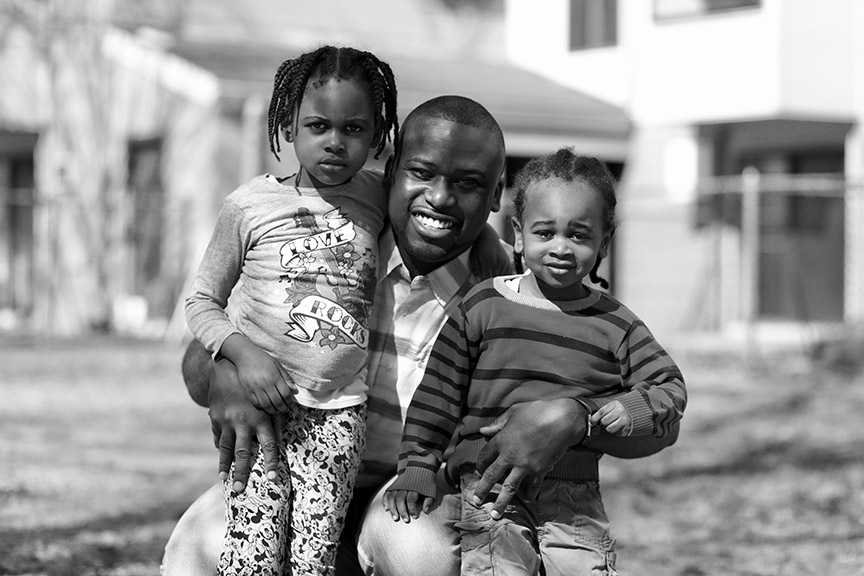

Since immigrating to the U.S. in 2000, Valcourt has managed to grow a large family in Framingham while sending much of his earnings back to his home country. He estimates he only makes about $3 per hour from Uber after vehicle expenses, but it helps him offset normal transportation costs by paying for his car and gas.

Once he cashes out for the day, Valcourt has immediate access to his earnings and doesn’t have to wait for a paycheck. He could either use the money to buy lunch if he’s in a rush or to send $1,000 to Haiti if he has enough saved like he did in March.

Despite the challenges he faces on the road every day, Valcourt believes a rideshare gig is a good option for immigrants. He believes that, while not the only factor, Uber has helped him with English, and he likes having the ability to be paid immediately.

“This is a great country with a lot of opportunity, but you have to fight hard,” Valcourt said. “You have to keep maintaining the best you can to get there.”

Immigrants often face hardships and obstacles that are atypical to the average American, but some of those who work in the gig economy have found a way to make their dreams more of a reality.

Delmy Sanabria worked for Amazon Flex, a package-delivery gig, for a while before she started doing Uber a few months ago to help pay the bills, and her husband has been driving full-time for Lyft since they got married a few years ago.

Sanabria, 22, and her husband are immigrants from El Salvador. She is a “Dreamer,” having moved here illegally as a child in 2005, and her husband has been a naturalized U.S. citizen for several years. The extra money from doing gigs is helping them go to school and save up for a house, but both are working all the time.

The gigs work for Sanabria and her husband because of the flexibility with their schedules, but they don’t want to drive for the rest of their lives. She is studying business but eventually wants to transfer to Lesley University to study accounting, and her husband is studying media.

“It’s good in the sense that we need the money,” said Sanabria, 22, who also works as a nanny on the side. It's just easy to just hop in a car and drive.”

Despite its problems, driving for Lyft has allowed Wambere to work full-time at a domestic-abuse shelter, a new job he finds deeply satisfying. He’s also able to focus on his education and his passions without worrying about his or his family’s safety, and he can work whenever he wants. More importantly, he can make a living off of it.

While he would love to settle down and own a home one day, Wambere doesn’t see that happening in his near future. He says that about 80 percent of his total income goes back to his family in Uganda and other LGBT individuals suffering throughout the world.

“I just feel like I'm one of those lucky people who can be able to sustain myself and also be able to help somebody,” Wambere said. “I had to swallow my pride and say I have to do what I have to do, and here I am. I'm happy, and everything is moving on.”