Before the break, we at the NULab for Texts, Maps, and Networks and Digital Scholarship Group had the pleasure of hosting Micki Kaufman, the Modern Language Association’s Director of Information Systems. A doctoral student in US History and a Digital Fellow at the CUNY Graduate Center, Kaufman brings her previous professional background as both project manager and information technologist to her currently academic research and pedagogy. On November 18th, 2015, Kaufman joined our NULab Project Workshop to dialogue about the overarching theoretical and methodological concerns of her research–which most significantly incorporates text analysis and data visualization–while demonstrating for us her choice of tools and their associated strengths and shortcomings. Following our seminar and a visit to the DSG’s Open Office Hours, she delivered a talk titled, “Everything on Paper Will be Used Against Me: Quantifying Kissinger,” in which she discussed in more detail her current project of the same name.

“Quantifying Kissinger” is a computational analysis of Henry Kissinger’s correspondence from 1968 to 1977, much of which was during his service as Richard Nixon’s National Security Advisor and, later, Secretary of State. The mandate for this distant analysis, she narrates, comes from within the administration itself via a 1982 interview with Nixon’s Domestic Affairs Assistant John Ehrlichman, who charged historians with listening to analyzing all of the administration’s correspondence before characterizing it. It was by framing her work in this way that she, exhibiting an awareness of the place of the Digital Humanities in relation to the disciplines, reported staking out “a space in the argument that [historical] traditionalists can’t contest.”

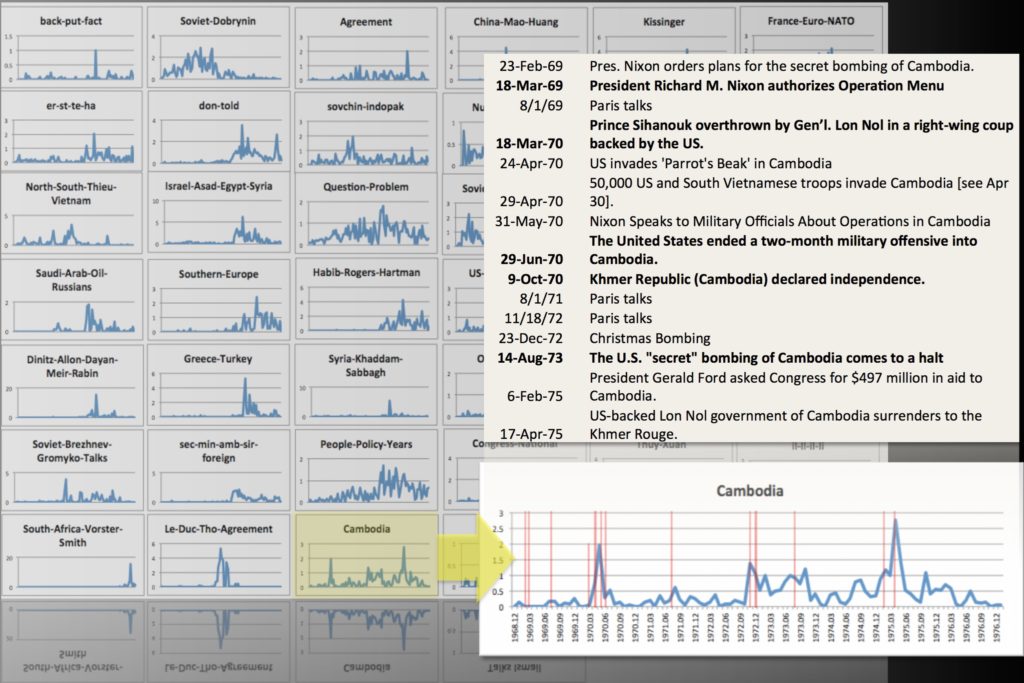

Her work adds a linguistic dimension to the scandalous conversation surrounding Kissinger’s humor and seduction alongside his secrecy and violence. Parsing the meeting memoranda (“memcons”) and teleconference transcripts (“telcons”) from Kissinger’s office, approximately 57K web pages containing about 18K documents recently declassified from the National Security Archive, Kaufman brings her historical interest in the “seem[ingly] paradoxical” Kissinger to read his correspondence distantly with a number of techniques: word frequency analysis, colocation analysis, topic modeling, sentiment analysis, and the plotted or force-directed network-mapped visualization of their results.

Kaufman related that her corpus of text, despite its declassification, was not entirely straightforward to assemble. Because of her need for comprehensive and consistent metadata for an informed and nuanced analysis, she wrote code to incrementally query ProQuest’s privatized curation of the public domain documents within the confines of her institution’s licensing agreement. She joked, but not without gravity, about the “C.Y.A.-ing” she did in anticipation of the following exchange between the company and her and her librarian. Kaufman’s attention to the “deep and pervasive” issues of access in her research was mirrored by that of access to her presentation: she took the time to ensure that none of the audience was color blind and unable take full interpretive advantage of her projected network diagrams and charts.

Moreover, Kaufman’s concern over access and accessibility manifested itself in her methodology and its relationship to a tradition of disciplinary gatekeeping in computing. Avoiding privileging the gendered and defended space associated with coding in data mining, which Bethany Nowviskie has called “a gentleman’s sport,” Kaufman has consciously used graphical user interface tools instead when possible in her work. While she wrote the code needed to massage the data and metadata into the forms necessary for her analysis (“be scrappy,” she recommends), she tokenized and analyzed her text with GUI tools like Laurence Anthony’s AntConc and curated and visualized the resulting data in Microsoft Excel. She then compared the results derived from those tools to the sometimes seemingly paradoxical results from command line-oriented software like David McClure’s Textplot and the Mallet topic modeling package, privileging neither.

Kaufman’s scholarship places significant emphasis on play and the “nescience,” in her words, of any approach she might take in her analysis. While she mentioned the importance of asking “questions of the dataset before one ever clicks ‘process’,” these words recommend deduction only on a surface level, given that she asks these same questions of her data with multiple sets of tools in conversation. She, for instance, compared the computer-generated list of themes from her topic modeling with the human-indexed list of topics in the metadata of her corpus.

For Kaufman, quantitative reasoning does not trump interpretive reasoning. Distant reading can be used as a guiding tool, to figure out where to close read, as much as a tool to “validat[e]” close reading. She similarly stressed in her talk that visualization works less for her as a noun, but more as a verb; visualization is a process, she avers, rather than a product, a tool she uses to “chart a path of epistemology.” Most importantly to her approach, I concluded from her visit, was to acknowledge but deliberately disregard, when mapping and traveling these paths, the expectations normally set and boundaries normally drawn, if not quite in the manner of the subject of her study. What she didn’t do, she says, was “wait to master the tool[s] to start.”

This is valued advice coming from a fellow graduate student doing meaningful work, in multiple spheres, to continue shaping the Digital Humanities as a field. Visit her project’s website for (interactive) visualization and discussions of her findings on the Kissinger correspondence. For more information on Micki Kaufman’s trajectory and work as a whole, visit her website www.mickikaufman.com and follow her Twitter feed, @MickiKaufman.