Next: Oscillatory Motion

Up: Motion in a central

Previous: Exercise 2.3

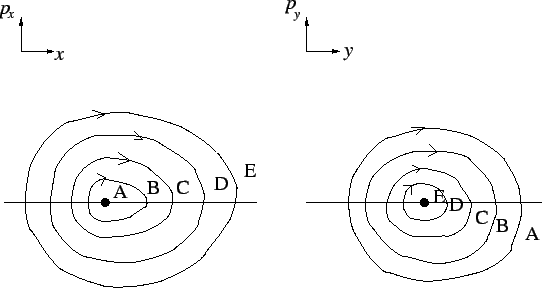

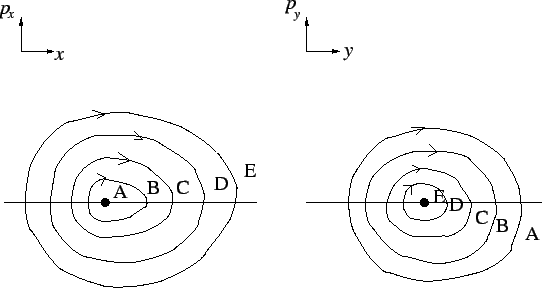

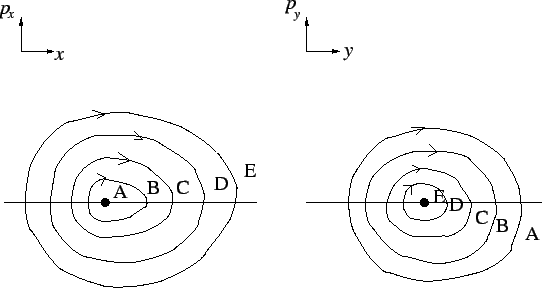

Figure 6:

Trajectories of a particle in a two-dimensional separable

potential as they appear in the  and

and  planes.

Several trajectories corresponding to the same energy but different

initial conditions are shown. Trajectories A and E area the limiting

ones having vanishing

planes.

Several trajectories corresponding to the same energy but different

initial conditions are shown. Trajectories A and E area the limiting

ones having vanishing  and

and  , respectively

, respectively

|

Let's ``complicate'' things a little bit.

We know that all the problems described above can be expressed

elegantly using the Hamiltonian formalism. Let us consider a particle

of mass  moving in a potential

moving in a potential  in two dimensions ans assume that

in two dimensions ans assume that

is such that the particle remains confined if the energy is low

enough. The momenta conjugate to the two coordinates

is such that the particle remains confined if the energy is low

enough. The momenta conjugate to the two coordinates  area

area

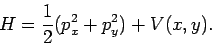

. The Hamiltonian (the energy!) takes the form

. The Hamiltonian (the energy!) takes the form

|

(37) |

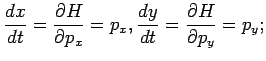

Given any particular initial values of the coordinates and momenta, the

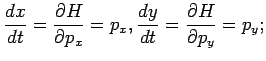

particle's trajectory is specifies by their time evolution, that is

governed by four first-order differential equations (Hamilton's

equations):

| |

|

|

(38) |

| |

|

|

(39) |

For any  , these equations conserve the energy

, these equations conserve the energy  so that the

constraint

so that the

constraint

restricts the trajectory to a three-dimensional manifold embedded in the

four dimensional phase space.

The Hamiltonian is said to be ``integrable'' when there is a second

function of the coordinates and momenta that is also a constant of

motion; the motion is thus constrained to a two-dimensional manifold

in phase space. Two familiar kinds of integrable systems are separable and central potentials.

In the separable case

where  are independent functions of only one variable, so that

the Hamiltonian separates in two parts and

each coordinate can be solved independently,

are independent functions of only one variable, so that

the Hamiltonian separates in two parts and

each coordinate can be solved independently,

The motions of  and

and  are therefore decoupled form each other and

each of the Hamiltonians is separately a constant of motion.

are therefore decoupled form each other and

each of the Hamiltonians is separately a constant of motion.

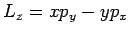

In the case of a central potential,

so that the angular momentum  is the second constant of

motion and the Hamiltonian can be written as

is the second constant of

motion and the Hamiltonian can be written as

where  is the momentum conjugate to

is the momentum conjugate to  . The additional constraint

on the trajectory makes the system tractable reducing the problem to

les variables. All the familiar analytically soluble problems in

classical mechanics are those that are integrable.

An analysis of phase space suggests a way to detect integrability.

Consider for instance the case of a separable potential, Because the

motions of each of the two coordinates are independent, plots of the

trajectory in

. The additional constraint

on the trajectory makes the system tractable reducing the problem to

les variables. All the familiar analytically soluble problems in

classical mechanics are those that are integrable.

An analysis of phase space suggests a way to detect integrability.

Consider for instance the case of a separable potential, Because the

motions of each of the two coordinates are independent, plots of the

trajectory in  and

and  planes should look as in

Fig.6. Here, we assumed that each potential has a

minimum value of 0 at particular values of

planes should look as in

Fig.6. Here, we assumed that each potential has a

minimum value of 0 at particular values of  and

and  respectively.

The particle moves on a closed contour in each of these two-dimensional

projections of the four-dimensional phase space, each of them looking

as a on-dimensional motion. The areas of these contours is associated

to the total energy (

respectively.

The particle moves on a closed contour in each of these two-dimensional

projections of the four-dimensional phase space, each of them looking

as a on-dimensional motion. The areas of these contours is associated

to the total energy ( and

and  ). Since the total energy must be

conserved, as one varies the initial conditions, one contour shrinks,

and the other grows. In each plane there is a limiting contour that is

approached when all the energy is in one coordinate. The fact that

these contours are closed signals the integrability of the system.

). Since the total energy must be

conserved, as one varies the initial conditions, one contour shrinks,

and the other grows. In each plane there is a limiting contour that is

approached when all the energy is in one coordinate. The fact that

these contours are closed signals the integrability of the system.

How can we obtain this information from the trajectory alone? Supouse

that at every time we observe one of the coordinates, say  , pass

through zero, we plot the location of the particle in the

, pass

through zero, we plot the location of the particle in the  plane. If the periods of the

plane. If the periods of the  and

and  motions are incommensurate

(i.e. their ratio is an irrational number), then, as the

trajectory proceeds, these observations will trace out the full

motions are incommensurate

(i.e. their ratio is an irrational number), then, as the

trajectory proceeds, these observations will trace out the full

contour; if the periods are commensurate (i.e. a

rational ratio), then a series of discrete points around the contour

will result.

contour; if the periods are commensurate (i.e. a

rational ratio), then a series of discrete points around the contour

will result.

Next: Oscillatory Motion

Up: Motion in a central

Previous: Exercise 2.3

Adrian E. Feiguin

2004-06-01

![]() moving in a potential

moving in a potential ![]() in two dimensions ans assume that

in two dimensions ans assume that

![]() is such that the particle remains confined if the energy is low

enough. The momenta conjugate to the two coordinates

is such that the particle remains confined if the energy is low

enough. The momenta conjugate to the two coordinates ![]() area

area

![]() . The Hamiltonian (the energy!) takes the form

. The Hamiltonian (the energy!) takes the form

![]() , pass

through zero, we plot the location of the particle in the

, pass

through zero, we plot the location of the particle in the ![]() plane. If the periods of the

plane. If the periods of the ![]() and

and ![]() motions are incommensurate

(i.e. their ratio is an irrational number), then, as the

trajectory proceeds, these observations will trace out the full

motions are incommensurate

(i.e. their ratio is an irrational number), then, as the

trajectory proceeds, these observations will trace out the full

![]() contour; if the periods are commensurate (i.e. a

rational ratio), then a series of discrete points around the contour

will result.

contour; if the periods are commensurate (i.e. a

rational ratio), then a series of discrete points around the contour

will result.